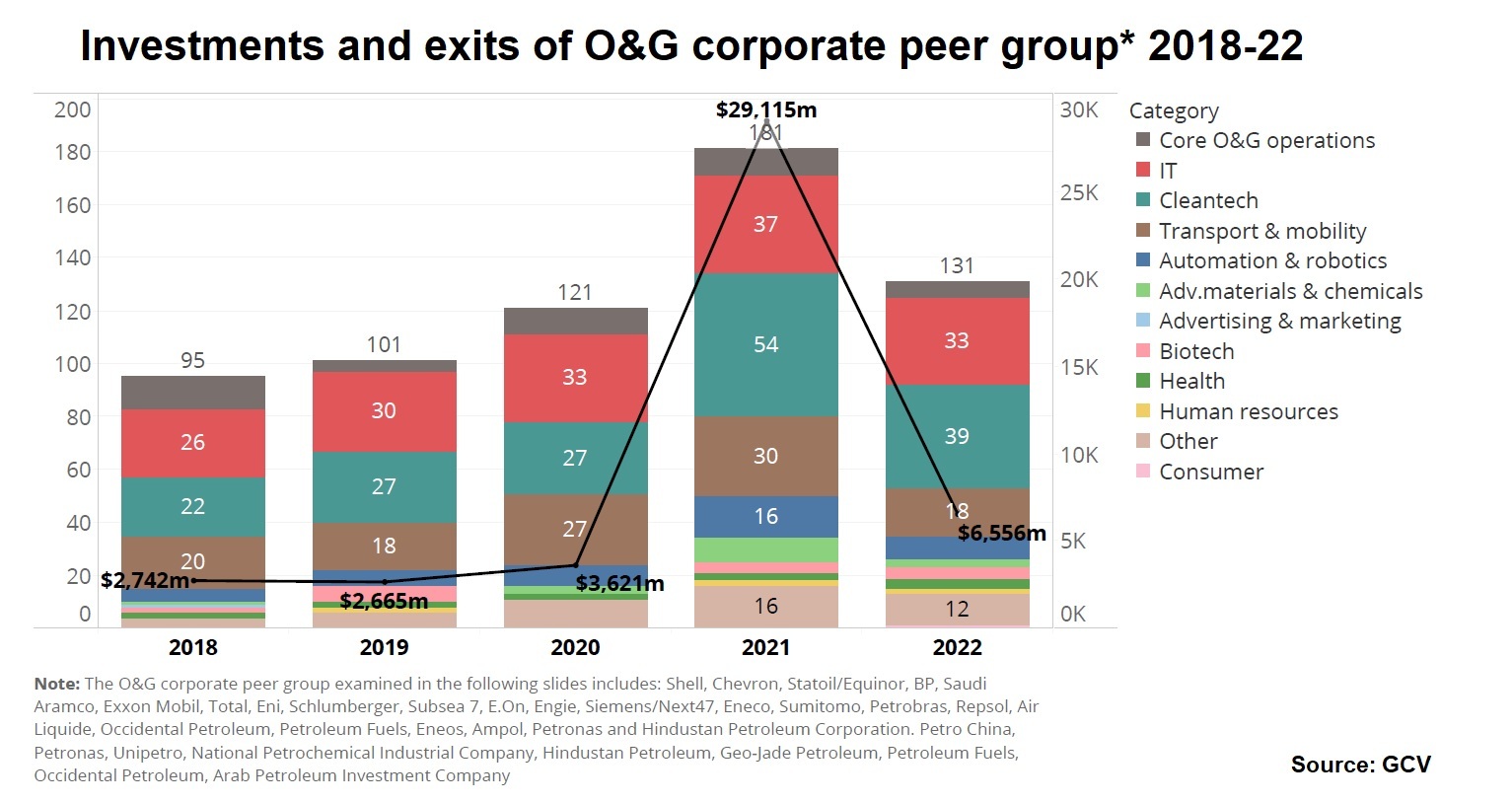

Oil and gas corporate venturers continued to participate in deals at roughly the same pace during the third quarter, but the total estimated valuation of those deals has dropped from the previous year.

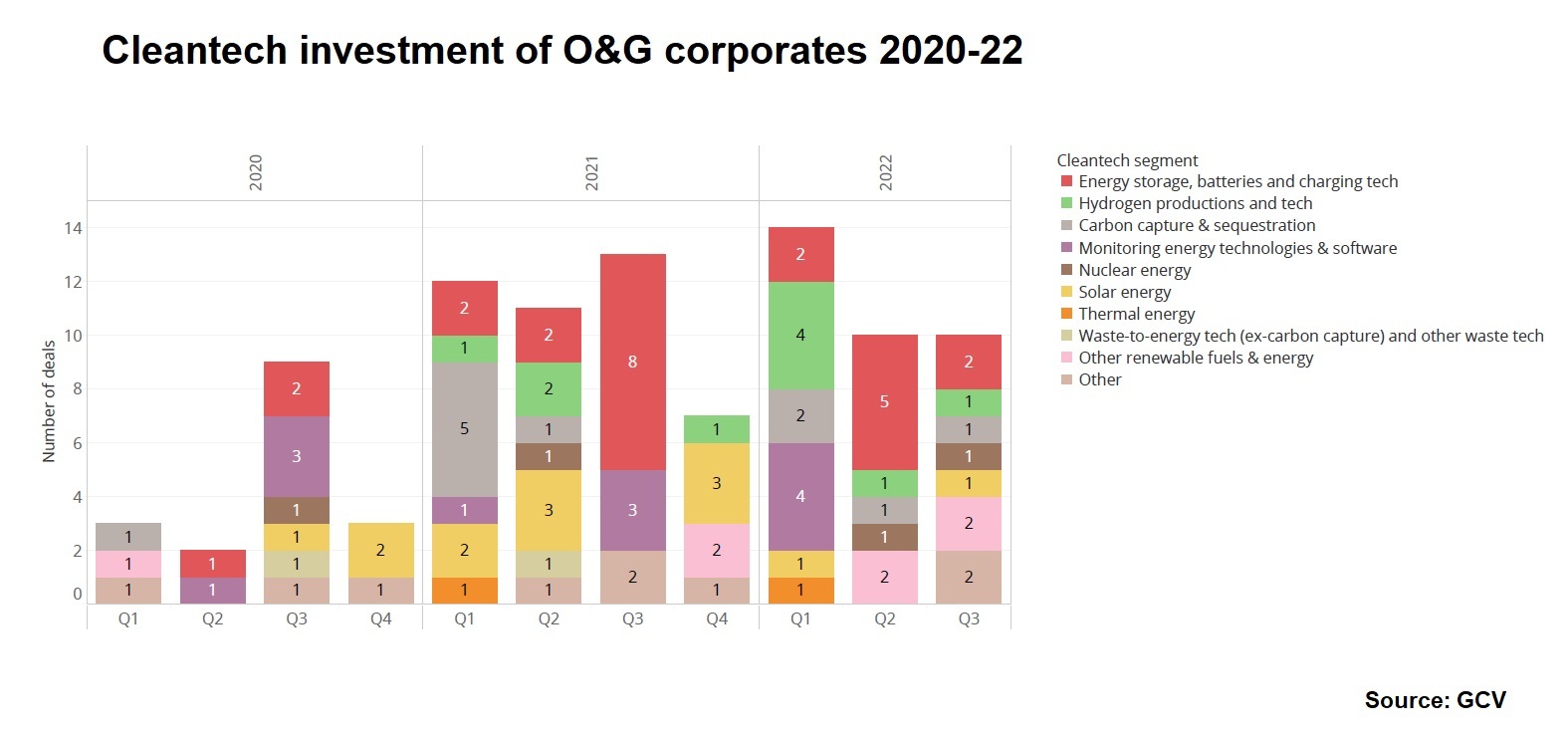

Cleantech deals are the only exception –as the energy sector reacts to a need to decarbonise, these deals have remained in high demand.We only saw a few exits, reflecting a lack of appetite in public and M&A markets.

All the while, the macroeconomic climate for commodity prices driving the sector remained generally favourable. There are, incidentally, some reasons to hope that Europe will successfully stave off a large-scale energy crisis this winter, despite Russia’s attempt to weaponise its natural gas supplies.

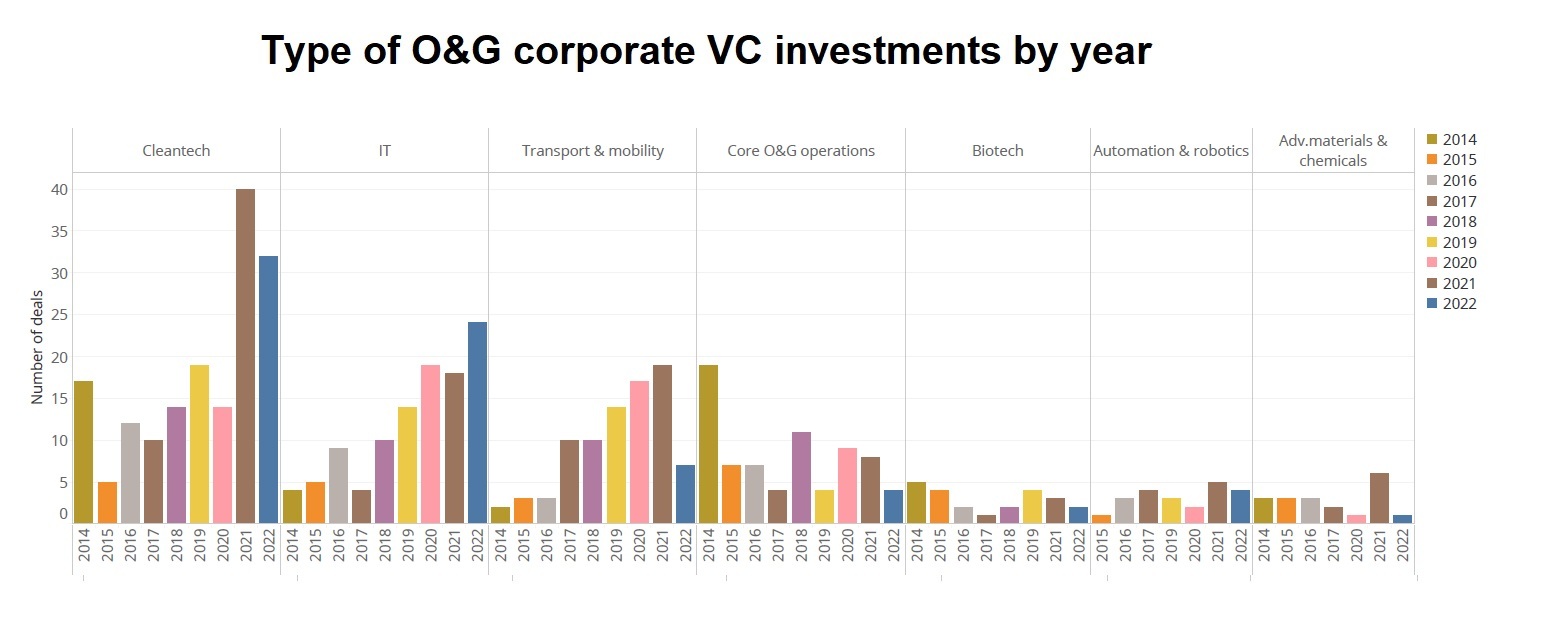

Figures from the first three quarters of this year show 131 transactions involving a corporate investor in the oil and gas sector, which would put the sector on track to reach a similar number of deals for the entire year as in 2021, when there were a total of 181 transactions.

However, the total valuation of those 131 deals stood at $6.6bn, just a fraction of the $29.11bn bumper deal value of 2021, when a flood of liquidity and accommodative monetary policy elevated valuations amid buoyant public and M&A markets.

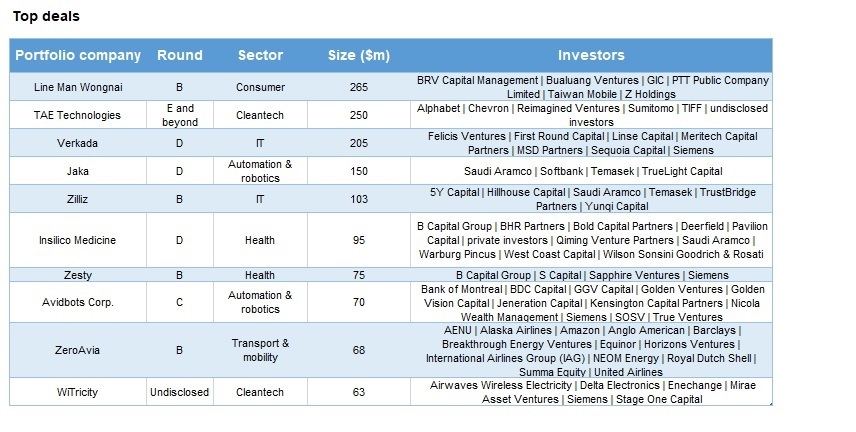

Deal count has remained the most robust in cleantech, IT and transport –the non-core areas oil and gas peers tend to invest in the most. The average size of deals in sectors in which oil and gas corporate venturing peers participated, amounted to $62.59m in 2022 so far, slightly higher than the average in 2021 ($61.84m). Both of these figures represent a surge from previous years.

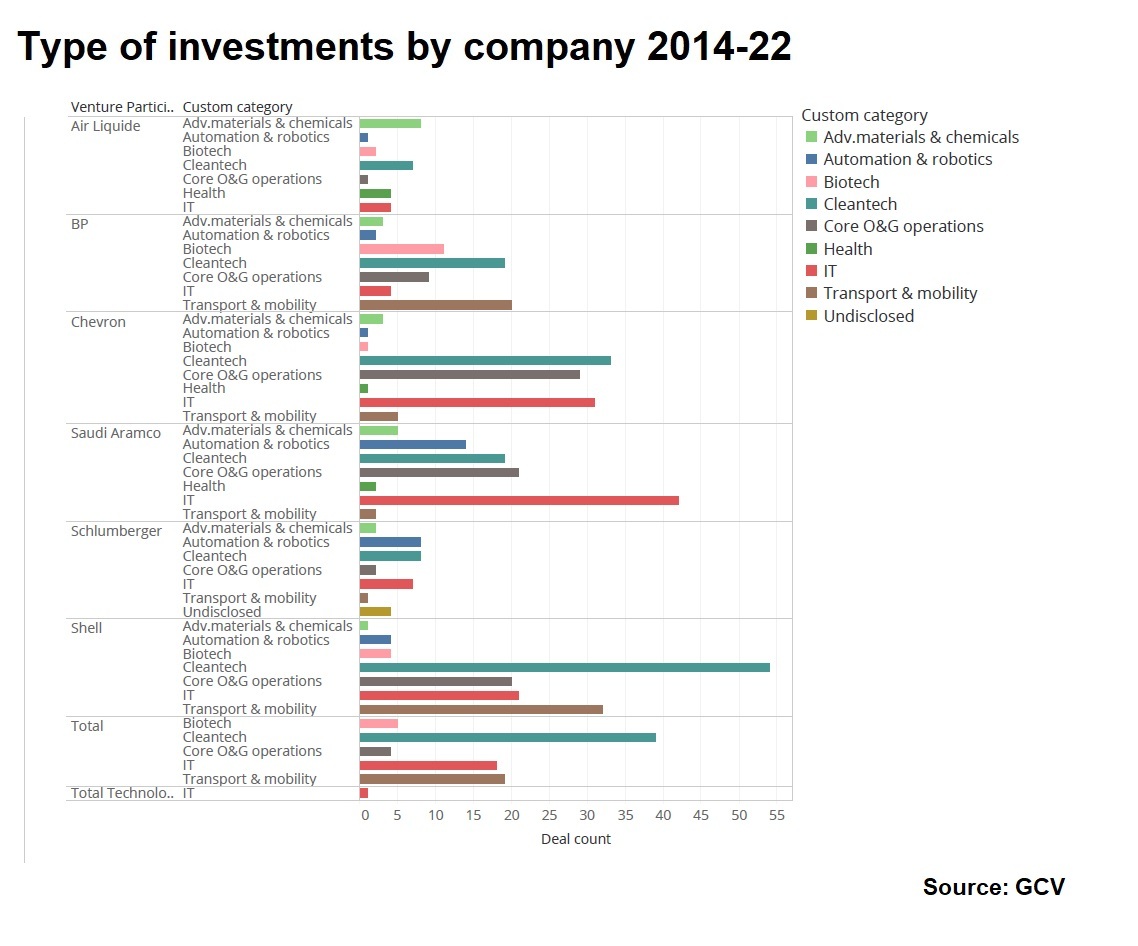

Chevron and Saudi Aramco have been leading the charge, with investments in cleantech and IT since 2014, while BP and Shell have most investments in transport startups in this peer group.

Energy storge powers on

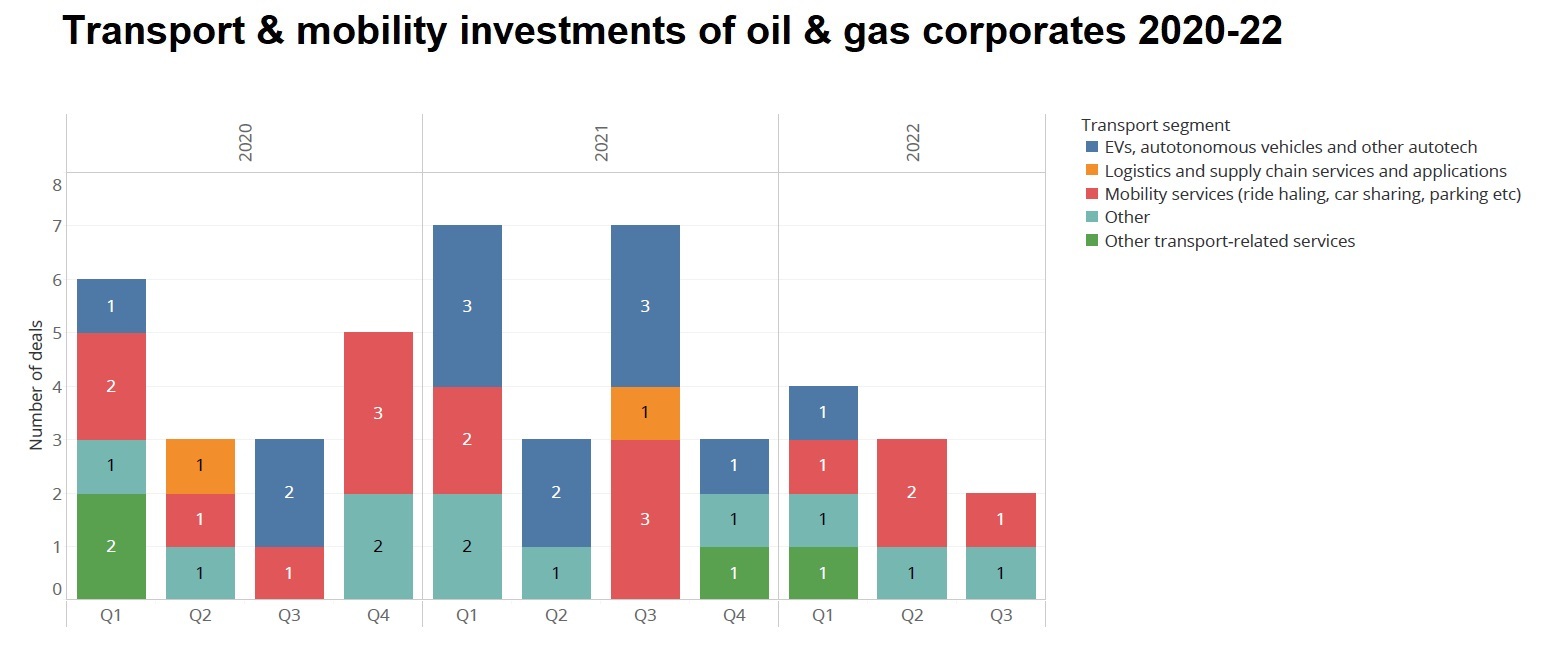

In terms of subcategories, batteries and energy storage, as well as hydrogen-related technologies have been some ofthe most popular investments in2022.As for the transport and mobility space, autotech (especially electric vehicles tech) and various mobility-related services have been the most popular subcategories for this year so far.

Oil price still on the rise

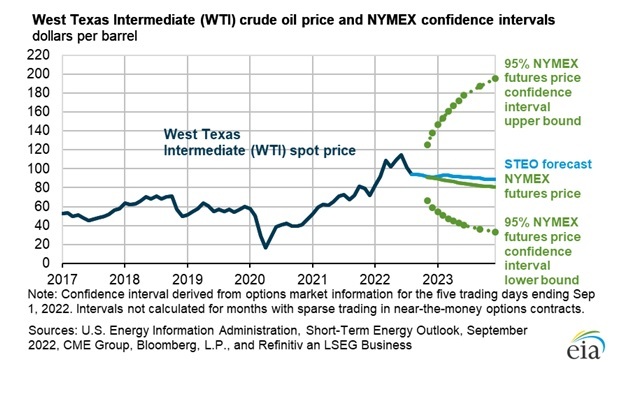

Investments from oil and gas majors have been steady, even in a time of turbulence and wild swings in commodity prices. In Q2 2020, when the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic broke out and global stay-at-home orders were imposed, pressures on both the demand and supply side made the oil price fall to less than $20 per barrel, down from $50-$60 previously. WTI futures even entered negative territory in April for technical reasons at the time.

Since then, oil prices have moved up considerably and appear likely to sustain their levels in the short run, given the overall supply situation. By the end of the third quarter of this year, WTI was trading at about $80 per barrel, having corrected down from year maximums of around $120 per barrel.

However, the future prices have started going up since that pullback and stood at around $92 at the time of writing. The catalyst for this uptick was the OPEC countries’ announcement of production cuts, which, along with ongoing geopolitical turmoil, are likely to offset downward pressure, driven by concerns on drop in demand during a probable recession. The US government has called the decision “short-sighted”, but it is unclear how it will react to it yet.

Earlier this year, analysts from investment banks had set wide-ranging price targets for crude –from the most optimistic from JPMorgan ($380 in one scenario) to the gloomiest from Citi, setting it at $65 per barrel.

The US Energy Information Administration’sShort Term Energy Outlook report from September 2022, however, gives a more balanced view. It expects the WTI benchmark to remain between $80 and $100 in the short run. The report also foresees retail gasoline prices staying around $4.28/gallon in 2023.

Shareholders of many oil and gas majors may be concerned about governments imposing a windfall tax on these businesses, particularly in Europe. While this tax may help assuage the energy crisis for society, it would mean potentially fewer resources for corporates to dedicate to investing in innovation.

Europe’s gas crisis

By now, most of the world is aware of the gas provision situation in Europe. Many are expecting a cold winter ripe with recessionary challenges. Mounting pressure on the price of natural gas, however, seems to have eased.

According to oilprice.com, gas prices hit $140/MWh, the lowest European benchmark since July. The recent drop is attributed to increased imports of liquefied natural gas into Europe and milder-than-expected autumn weather. In addition, higher nuclear power generation in France has also boosted electricity supply across the continent. Europe is coping with the acute gas crisis, which will cost it in the short run, but is the weaponisation of natural gas supply by Russia sustainable longer term?

The military conflict has forced the EU to replenish gas storage facilities that, according to Reuters, were 91% filled by the beginning of October 2022, having reached its November target of 80% well ahead of time. The closure of the Nordstream pipeline has undoubtedly raised costs in Europe but, ultimately, may hurt Russia more. Energy revenues from exports reportedly make up almost 60% of all government revenue in Russia.

Currently, the Ural crude, the Russian grade of crude oil, sells at a steep discount to Brent and WTI. Bloomberg recently reported that this is why energy revenues for Russia have reached a year-on-year low. This does not take into account the economic effects of sanctions imposed on Russia by western countries.

All this is to be kept in mind in the context of waging war in Ukraine –an expensive undertaking by itself. Recently, the Russian government began conscripting from the civilian population, as well as recruiting soldiers from prison inmates. Such measures suggest Russia is far from winning the economic war. This is not to say that resolution of the military conflict and tensions with the west necessarily lies around the corner. However, examining contrarian arguments helps to elucidate facts often overlooked by sensationalist headlines.

Investing in solutions

We have consistently observed, over many years, a shift in focus among oil and gas corporate venture investors, still evident today and likely to continue to hold in the post-pandemic world. Many of the disclosed deals by such investors concentrate in non-core areas, primarily in IT and cleantech, as well as transport and mobility.

Such non-core businesses possess the most disruptive potential to the core business of oil and gas companies. Media, governments and society overall reinforce the notion of the necessity and inevitability of a low-carbon world and, ultimately, the complete phaseout of fossil fuels.

The increasing adoption of electric vehicles may affect a considerable part of the customer base of oil and gas companies, though how quickly still remains debatable. There has also been a growing digitisation of industrial activities, which exerts a tangible impact on production and efficiency.

Despite this focus elsewhere, it is not unreasonable to expect more investments in core oil and gas technologies, particularly in companies whose solutions provide significant cost-savings or make operations less contaminating. Such investments will continue to form part of the portfolios of CVCs from the sector due to its capital-intensive nature, contingent on the up and down swings of commodity prices. This holds true particularly in a time of rising oil and gas prices and limited refining capacity.

In the long run, however, corporate venturing arms of oil and gas incumbents are likely to continue to hold more strategic views rather than purely financial ones. In addition to investing in technologies that may profoundly disrupt their sector, strategic benefits may come in the form of building an ecosystem, finding suppliers or helping business units with specific technical challenges.