Energy companies are best placed to back the deeptech startups working on climate change solutions, especially as the investment climate remains challenging, according to a recent report by law firm Norton Rose.

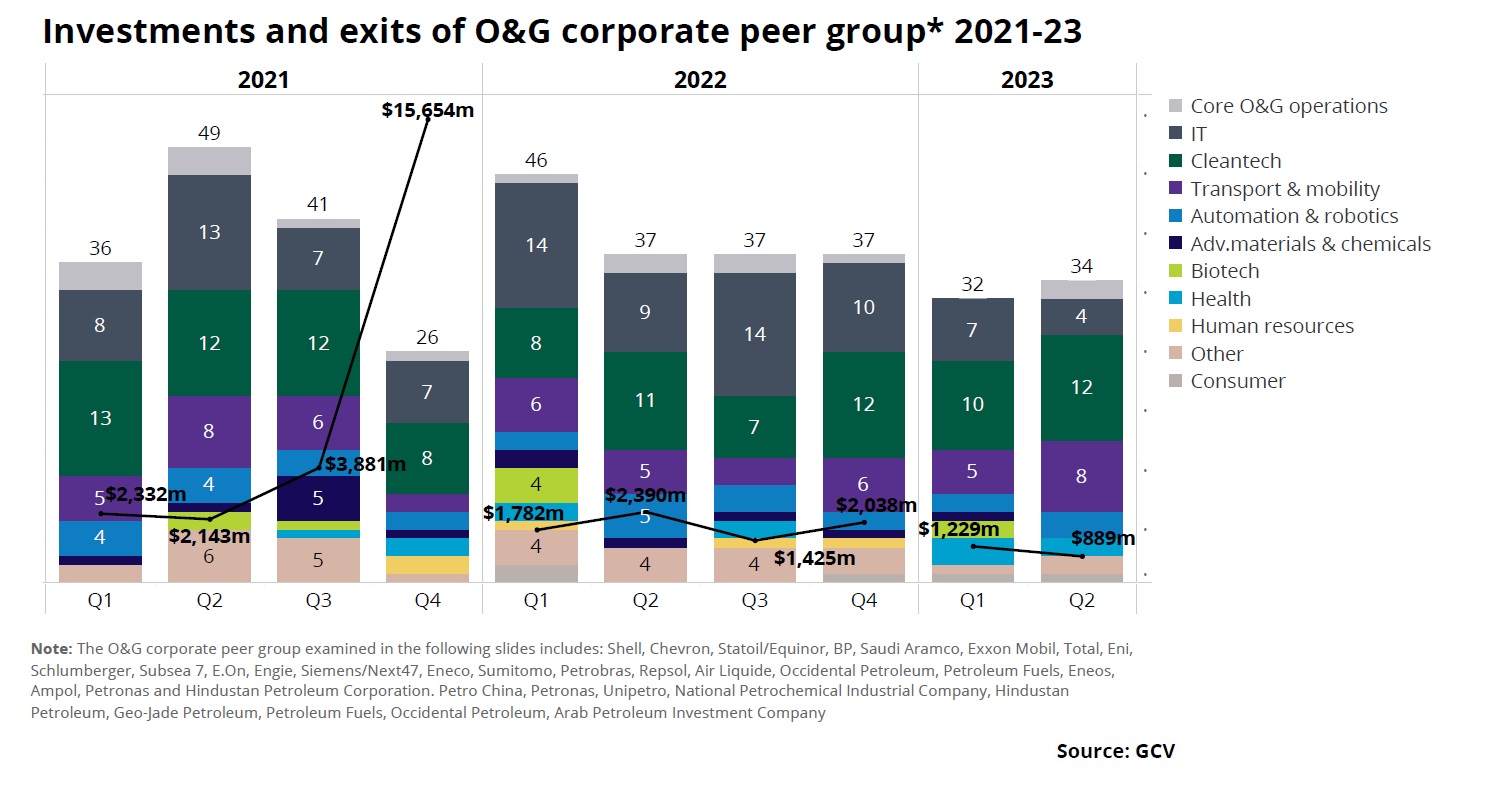

But oil and gas companies have been pulling back from investing, much like other investors, over the past year. The dollar value of deals done by a group of oil and gas majors tracked by Global Corporate Venturing, nearly halved in the first half of 2023, compared with the same period in 2022. The number of deals done by this group of companies, which includes Shell, Chevron, BP and Saudi Aramco, also fell by 20%.

On a positive note, investments in cleantech-related startups have held up relatively well amid a general decline. Cleantech has become a relatively larger proportion of the deals that are still being done, accounting for about a third of all the investments by energy companies. Some areas of cleantech, such as carbon capture utilisation and storage have seen a rapid increase in the amount of investment, according to PwC study published at the end of 2022.

A considerable financing gap

But the Norton Rose whitepaper suggests more support may be needed, as there is a “considerable financing gap” for the deeptech startups working on climate change solutions. These companies— for example those developing cleaner fuels, or energy storage — require heavy capital expenditure to build production facilities and testing labs, and are often shunned by traditional venture capital firms, which tend to favour asset-light business which promise fast growth.

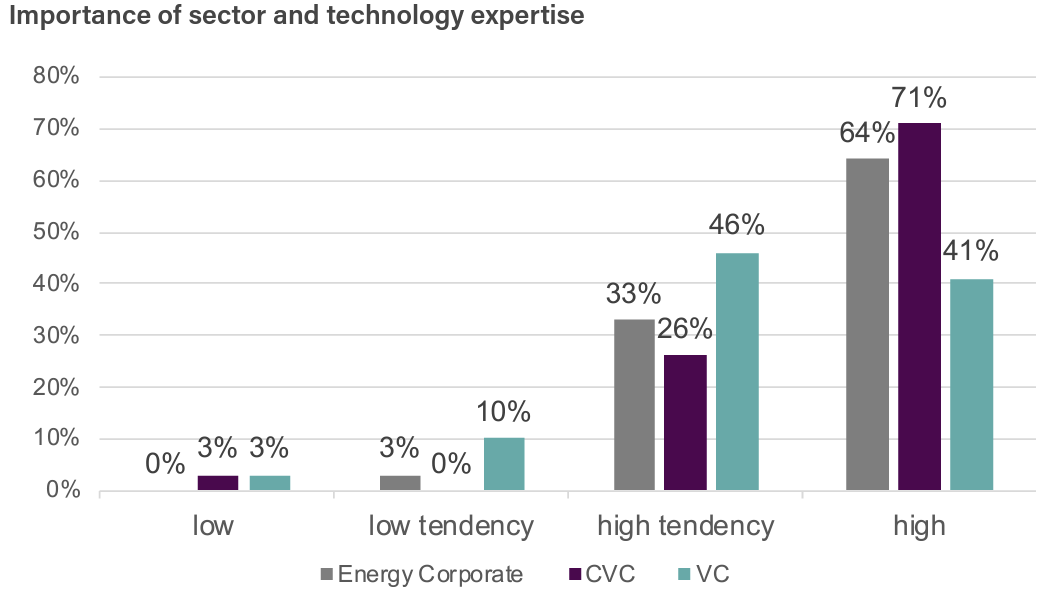

Corporate investors are also often in a better position than financial investors to assess the merits of technology-heavy startups as they have their own in-house experts to call on for the due diligence.

“CVCs could exploit a real competitive edge over other investors as they tend to have the technical and market expertise to assess the inherent risks,” the authors write.

Interviews carried out in the study showed that corporate investors gave much more weight to technical expertise and market knowhow than their financial investor counterparts when making investment decisions.

Moreover, corporate investors can, in some cases, take a much more long term view on investments as they are not tied to returning money to investors in a set period of time, as many VC funds are.

A retreat by energy companies from equity investment in startups may not be quite as stark as it appears however.

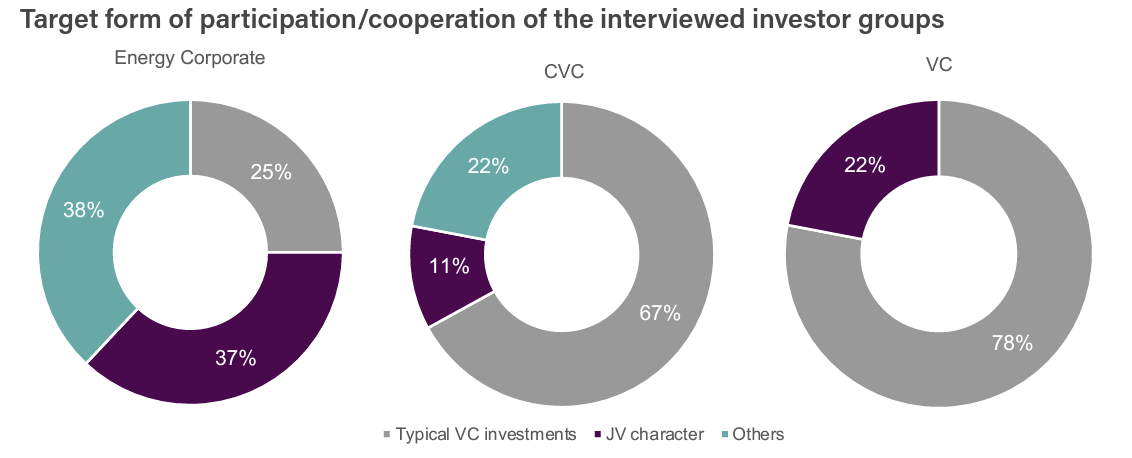

The Norton Rose study noted that energy companies interact with startups in a wide variety of ways, and taking minority investments in companies is a relatively small part of this. Typical startup investments only made up some 25% of the ways in which energy companies participated in the startup ecosystem. Another 37% of interactions involved joint venture-style arrangements where the corporation had more ownership, and a further 38% of engagements — shown in this chart as “other” — involved either looser collaboration with startups or venture building activities where the corporates set up their own startups internally.

A retreat from equity investing by energy corporates may to some extent be balanced by an increase in activity in these other areas.