Follow-on funding rounds was once the Achilles heel of corporate investors. A decade ago, CVCs had a bad reputation for not taking part in the later funding rounds of the startups they had invested in.

“It used to be that corporates would say: ‘We don’t know what our budget is going to be from year to year, so don’t look to us for later rounds’. I think that was part of the reason why corporates got a bad rap for not being dependable capital,” says Sandi Knox, partner at the law firm Sidley Austin.

“But I’m happy to see a very positive evolution over the past five to ten years where corporates understand the need to be a true partner to businesses. And part of being a good partner is being there for subsequent rounds.”

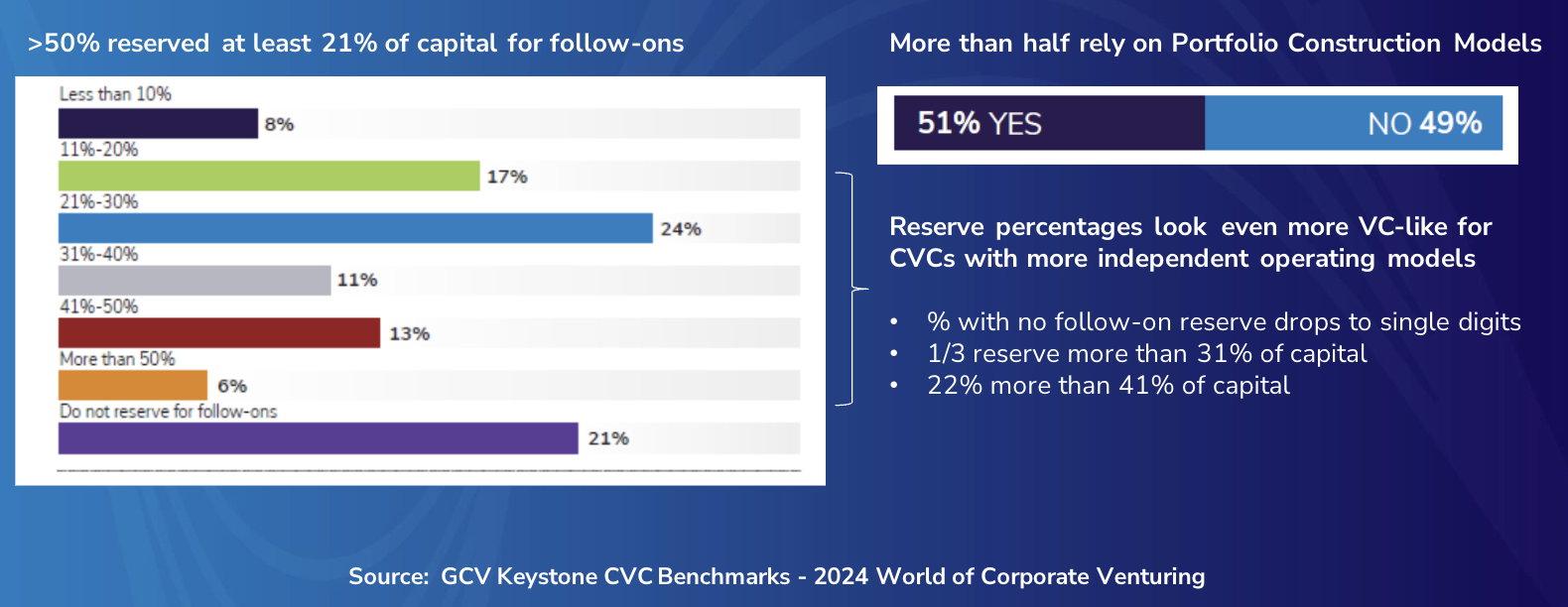

In fact, around half of CVC units reserve at least 21% of their capital for follow-on rounds, according to data from the annual Global Corporate Venturing survey. The percentage of CVC units increases even more when looking at those corporate venturing units with very independent operating models.

But follow-on rounds can still be tricky for a large proportion of CVC investors. What if the corporate parent doesn’t want to support a follow-on round? Are there ever any acceptable reasons not to invest in the next funding round of a portfolio company?

Knox, David Hayes, partner at Decarbonization Partners — and formerly a corporate investor with BP Ventures — and Crispin Leick, founder and managing director of EnBW New Ventures, came together to share their learnings in a webinar panel session moderated by Mark Klopp, an instructor at the GCV Institute and himself an experienced CVC investor. [Find out more about the in-depth CVC training offered by the GCV Institute here.]

Here is what they shared:

[Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the speakers only and not their organisations. They do not constitute legal advice.]

1. Not participating in follow-on rounds is a bad signal — for both the startup and the CVC

When a strategic investor doesn’t participate in the next funding round of a startup it has backed, this raises big questions for other potential investors, says Hayes.

“As a financial VC evaluating investment opportunities where strategics around the cap table are not participating, you wonder if that is a budget issue or a technology issue or a management issue.”

But even more crucially, says Knox, not doing follow-on investments gives a corporate investor a bad reputation, and leaves them excluded from the best deals.

“Your first few deals are important. If you signal to the market that you’re non-commercial, hard to work with, that you’re only in it for yourself, you’re not going to get the good deal flow. You’re not going to get invited to the competitive, most compelling deals,” she says.

As Hayes puts it, startup investment is a team sport — and a long one at that.

“It’s a long game to get these companies to the point of being successful. And if you’re not going to pull your weight, [if you’re not going to support them], you may find you stop being invited to play,” he says.

2. Declining follow-ons brings other disadvantages

It is not just reputational damage that corporate investors need to worry about. There are some tactical issues too if an investor opts to sit out of a follow-on round.

“You might start to lose visibility of what the company is up to, maybe you lose your observer seat because not participating might signal that you are leaning out from the company, and you no longer merit a seat in the boardroom,” says Knox. “Maybe your information rights start to get constrained. And maybe you’re just less a part of the conversation.”

3. There are a few acceptable reasons to not participate in a follow-on round

The panel was asked whether there were circumstances where it is acceptable for a company not to participate in a follow-on round. Leick was crystal clear on this.

“The only reason not to participate in my view is that the startup has not delivered what they promised. There can be no other reason.”

Hayes said that the default at Decarbonization Partners would be to participate in follow-on rounds. A lack of performance might be a reason not to invest, or if the startup had pivoted dramatically from its original business. If it started off as, say a producer of sustainable fuel but switched to producing diesel, then it might no longer be a fit for an investor with a sustainability brief.

A valuation that had been driven too high might also be a valid reason to pause.

It may also be acceptable to not participate in a round if the startup has plentiful offers for new funding and wouldn’t be harmed by a corporate investor not chipping in.

But if the startup is struggling to raise the next round, the corporate investor should not abandon them.

4. But a change of strategy by the parent corporation is NOT an acceptable reason

While a pivot by a startup might be a valid reason not to invest, a pivot by the parent corporation is not. Even if corporate strategy has shifted in a way that means there are no more strategic synergies with the startup, the corporation should still keep investing.

If the startup investment was made for financial as well as strategic gains, this shouldn’t be a problem, says Knox.

“If the strategic reason has gone away, hopefully there were other reasons that the corporate invested in this portfolio company,” she says.

Leick agrees that the CVC should not be drawn too much into serving corporate commercial needs. This means that that a shift in parent strategy shouldn’t mean a shift in commitment to a startup.

“I think it is paramount for a modern CVC organisation to strictly separate any investment activity from an operational commercial cooperation activity. There has to be a Chinese wall, otherwise, you run into constant trouble,” he says.

The key, says Hayes, is to think like a VC first, not as a corporate.

“Be a good VC. Invest dollars, try and make money on the return,” he says. “If you can get strategic value from some sort of collaboration, that’s awesome, but that’s upside.”

5. How do you make sure you can do follow-on rounds?

Have an independent structure

The best way to ensure you can commit to doing follow-ons is to have an independent structure for your CVC unit, and a dedicated fund, preferably an evergreen fund. That is what Leick created when he set up EnBW’s fund in 2016.

Leick says he worked hard to make sure that investment decisions, including decisions on follow-on rounds, were not made by corporate executives.

“The task of the investment committee is to discuss if this is a good deal, if the startup is developing well, if it fits the portfolio, what the exit is and so on. It has nothing to do with any strategic side discussion,” he says.

A specific capital commitment is also paramount, so that the investment team doesn’t have to go cap in hand to the corporate parent for every deal.

“If you don’t have a capital commitment, how can a startup take that risk [that you might not be able to follow on]?” asks Leick.

Make sure your investment committee is not filled with corporate people

Even if your investment committee doesn’t have quite the full freedom you’d like, you can improve things by making sure the committee at least includes the right kind of members. Leick says CVCs should make sure that “this investment committee is not filled only with some corporate players, but it’s also filled with external specialists, tier one VC partners and so on. I think these are important ingredients in order to [be able to] follow-on.”

Get pre-approvals for follow-ons

And when a CVC unit doesn’t have its own fund and an independent investment committee, one strategy that helps could be trying to get some kind of pre-approval for a certain level of reserves for follow-ons, says Klopp.

“If you can’t do that, then make sure the criteria [for a follow-on] is a very easy hurdle to get through and will not [require you] to go back and and fight for a follow-on,” he says.

Educate, educate, educate

CVC investors can do the groundwork early on by educating their corporate parent about the need to make follow-on investments.

“The key is educating and having those nuanced, complicated discussions that you need to have with all the stakeholders,” says Knox. “You’ve got to win the hearts and minds of the C-suite and your board and your key business leaders.” This takes time, so start early.

6. How much should you reserve for follow-on rounds?

It’s a little like the question about how long a piece of string is. A VC industry norm is something around a third of the fund to be set aside for follow-ons. But Leick is willing to be even more specific about EnBW’s methodology. The team will will generally invest some $10m in total per startup over several rounds. It will start with a $2m ticket, with the majority of the money reserved for follow-ons.

“We revisit these capital allocations at each round, of course, but even if there’s no round once a year we check if the allocation still adequate for the startup,” says Leick.

GCV was not permitted to fully quote what participants said in this written summary. But if you would like to hear the remarks in full you can watch the webinar replay below:

This webinar is part of GCV’s The Next Wave series of webinars. We run a webinar on the second Wednesday of every month, alternating between advice for CVC practitioners and deep dives into specific investment areas. Our next webinar will be Moving the goalposts – How to invest in a changing world of sports on June 2024. Register here to secure your place.