Venture capital (VC) in China has grown significantly since its establishment in the mid-1980s such that the level of VC investing is now second only to the US. Yet there have been few studies of the investment practices of Chinese VC firms, and none have compared these specifically with those in both Europe and the US, which have more mature markets and regulations, according to Arundale’s prior paper, Venture Capital Performance: A Comparative Study of Investment Practices in Europe and the USA.

The development of the VC market in China is closely related to government policies. In 1985 the Chinese Central Government issued the policy “Decision on the Reform of the Science and Technology System” and the first VC firm in China was launched in the following year. With a registered capital of about $10m from different government ministries, its primary function was to invest and provide loans for high-tech industry development. In 1991, further provisions issued by the Chinese State Council promoted the practice of VC in the high-tech industrial development zones. This led to the first joint-venture VC, a collaboration between the Shanghai Commission of Science and Technology (SCST) and IDGVC (former IDG Capital, the then-local corporate venturing unit of US-based International Data Group).

In 1995 and 1996, China successively issued regulations encouraging domestic non- banking financial institutions and Chinese-controlled foreign institutions to invest in domestic projects, and large companies, research institutions and individuals were permitted to participate in VC investment. In 2001, foreign VC institutions were allowed to invest in China. Since then a large number of foreign VC firms have entered the Chinese market, although these now only represent a relatively small proportion of the market; several foreign firms have left China recently

There are now generally three types of funds in China: independently owned, onshore domestic-invested funds in RMB, onshore government backed RMB funds and foreign funds in either US $ (offshore) or RMB (onshore). US$ funds tend to have larger funds under management than RMB funds and have longer-term capital from typical, though largely overseas, institutional investors. The main source of RMB funding is city government funds for promoting industry within that city, then from large corporates and wealthy individuals. Most government funds are RMB domiciled funds; some local VCs with previously RMB funds are now raising US $ funds with foreign capital for investing in China.

From data provided specifically to the authors by Preqin, government sources comprised just 4% of VC funding in 2019 with pension funds at 17% and corporates at 14%. Preqin found the median net internal rate of return (IRR) from inception of Greater China VC funds has exceeded that of Europe and USA, notably for 2009 and 2013 through 2017, reaching 59.3% in 2014 compared to 20.0% for Europe and 16.6% for US. However, the sample size of the Greater China VC funds is small, given the difficulty of sourcing such data.

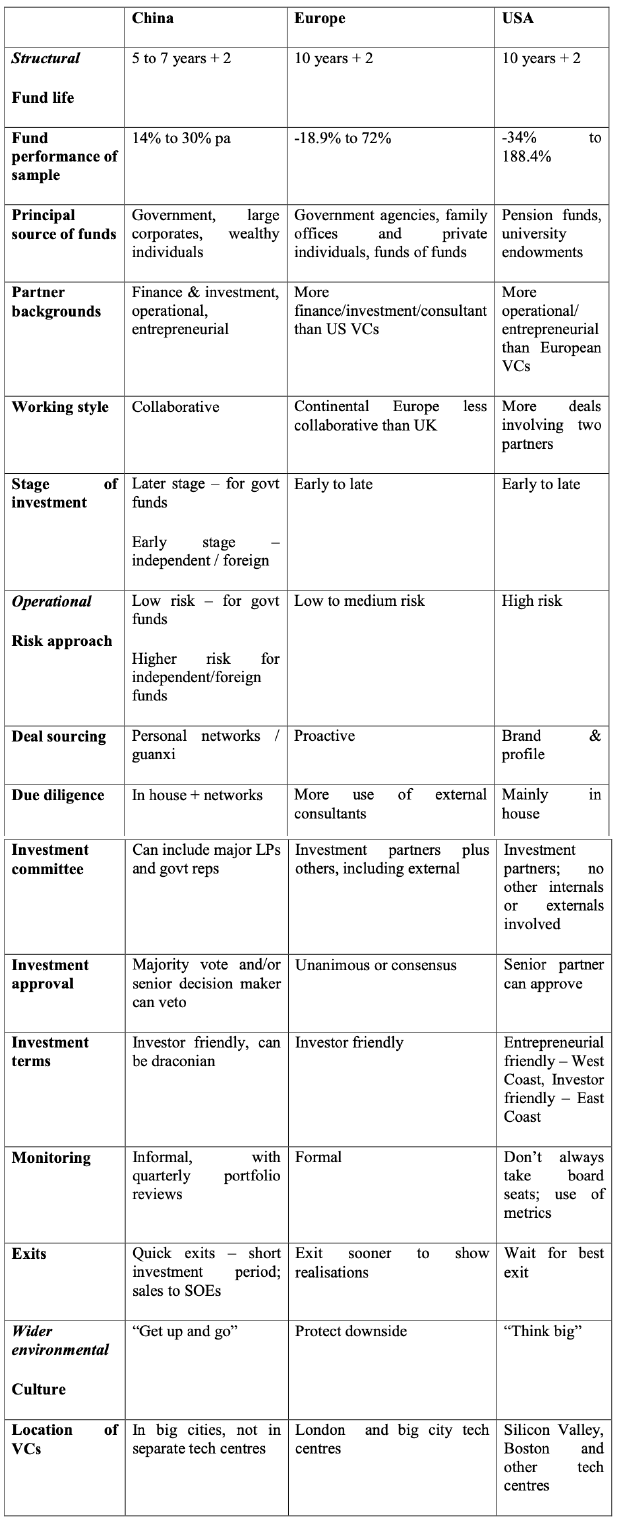

RMB funds are typically smaller than US$ funds. The typical life of a Chinese VC fund is seven years with extensions of up to two years compared to the norm of 10 years plus two years in Europe and the US. This tends to favour later stage investing with a quick route to exit.

Investment partners in Chinese VC firms come from a variety of backgrounds, including finance and investment, operational often from working with large technology companies, and entrepreneurial, much the same as the US firms in the earlier study where proportionately more partners with operational and, to a lesser extent, entrepreneurial backgrounds were engaged than was the case with European firms. The older generation of partners tend to be investment bankers, the younger generation are from operational and entrepreneurial backgrounds and have in-depth sector experience from working in those sectors and/or starting companies in those sectors.

There was evidence of Chinese investment partners working collaboratively together on deals, as was found particularly with US firms in the earlier study. Advisory boards of technical experts were engaged by some of the VCs in the study whilst others called upon their networks of technology experts from universities and large corporates on a deal by deal basis: “Our partners all have industry backgrounds, so they are familiar with the top tier persons in that industry and we have good relationships with the institutions and universities, so normally we’ll consult them as well.”

The use of advisory boards and / or networks of technical experts was similar in Europe and the USA to that in China.

RMB funds in the sample tended to invest at later stages where companies are closer to exit; US$ funds were prepared to invest in early and subsequent stages. European VCs are largely proactive in sourcing deals whereas US VCs rely more on their branding and profile in the marketplace to attract entrepreneurs.

However, Chinese VCs may be prepared to invest in ground-breaking technology because “they know that the growth will be exponential and there would be a very high return and so they’re willing to take the risk”.

The precise sectors that the more established VCs invest in China are often determined through relationships: “The guanxi network of relationships and as a result the sectors they end up with are absolutely all over the shop.”

Both state-backed and independent VC funds in China invested predominantly in the technology sectors, with a focus on semiconductors, big data, artificial intelligence, biotech and med/healthtech. In the earlier study there was no particular difference between European and US VC firms in terms of their stage and sector focus.

Differences in investment practices between Chinese, European and US VC firms and funds

In the earlier study it was apparent that UK/European VCs have fewer resources than US VCs to develop investment themes and so adopt more of a follower approach. In China, some VCs are more likely to be following on from an investment trend that has been set up in the US rather than looking at completely new innovative technologies, though others may carry out considerable research into sectors.

The operational aspects of VC firms in China concerned their investment practices. Government RMB funds adopted a lower risk investment strategy than US$ funds which is reflected in their investing in later stage companies.

Investment committees to approve investments were comprised not only of investment partners but also anchor limited partners and municipal government representatives, with the latter having votes and even veto rights in some instances.

Majority vote tends to prevail but a senior person may the ultimate decision maker, similar perhaps to the practice of senior partners in some US VC firms being able to railroad deals through the investment committee.

There may be separate investment committees for each fund. Government representatives largely observe but may have a vote. The chairman of the investment committee may have a veto but needs a vote or consensus to get a deal approved. At one government backed VC firm, committee decisions can be over-ridden by people higher up the management chain.

Investment terms used by Chinese VC firms were considerably more “investor friendly” than either European or US VCs with the Chinese enforcing onerous term sheet clauses on their investee companies. These included negative ratchets, common with state-owned funds, and if management teams fail to make their revenue or profits targets they might even have to pay cash or equity compensation to the VC. (See Box on UK’s security act)

On the other hand, investments which are strategic and not purely financial may also exhibit fairer terms and preference shares, often used by European and US VCs to limit downside exposure, are not used in China unless through an offshore holding structure as Chinese company law does not clearly state the legitimacy of preferred shares in limited liability companies.

In addition, Chinese company law does not permit use of the “safe note”, a type of convertible loan note. Government backed funds tend to be risk-averse and take considerable care about the security of their investments as reflected in their investment terms and through investing at later stages. If the government invests say as much as 40% in a fund they will want to have significant influence about which investments are made by the fund. “They all have the concept that you want to find a brilliant deal, own the whole of it and live happily ever after, so the whole concept of portfolio theory doesn’t apply.”

Syndication with other VCs, both local Chinese and foreign VCs, was common, as is the case with European and US VCs, though government backed VCs do not usually syndicate with foreign VCs. In the earlier study it was found that US VCs can be reluctant to syndicate with European VCs because of their lower risk propensity and more investor friendly investment terms.

In terms of monitoring post investment, this can be quite informal in China, with calls and social events more of the basis for keeping in touch with portfolio company performance rather than necessarily attending board meetings and reviewing reporting packs as would be the case in Europe and USA. Periodic portfolio reviews are however carried out formally often on a quarterly basis with more frequent discussion amongst the partners.

Government backed funds will certainly require regular updates on current investment values. Under a new regulation funds are now required to be audited annually and LPs provided with valuations.

Value adding activity is largely through leveraging contacts for the benefit of portfolio companies through the VC’s personal network and guanxi, much as is the case in Europe and US. Foreign investors in China are seen as weak in terms of adding value to their portfolios as they do not have “the right relationships”.

Government VCs can enable their portfolio companies to benefit from favourable local policies in terms of subsidies and public procurement. They also enjoy a greater chance of gaining approval for IPOs.

VCs in China pay much attention to the geographical location of projects due to concerns about the public policies of local governments and the supply of human resources in specific areas.

The state-owned economy and the political system has a large impact on the sector with VC activity heavily influenced by policy makers. The government will provide grants and support as leverage to the investor if projects are in accordance with the five-year plan but “if you’re trying to do something that’s outside the objectives of the five-year plan then forget it”.

The focus is more about selling to state-owned enterprises and meeting needs at the provincial or national level. One interviewee said: “The bulk of all commercial and capitalist activity isn’t really oriented towards capital markets as it is in the west it’s really oriented to servicing the needs of the nationalized state economy and so most businesses will exit by sale to a SOE [state-owned enterprise] or setting up a joint venture with a SOE.”

Another added: “The pace in China is quicker or faster than the pace in Europe so that’s a very normal thing; if in Europe you need 10 years to build a startup, in China maybe you just need five years to get the same level”