As the biggest economy in Latin America by far, Brazil has been at the vanguard of the region’s venture market for years. And corporate investors are starting to take up a bigger chunk of the dollar value of total startup investments.

“Just in Brazil in the past 2 years, we’ve had about a billion dollars of corporate commitment for corporate venture capital,” says Richard Zeiger, partner at MSW Capital, a CVC fund manager.

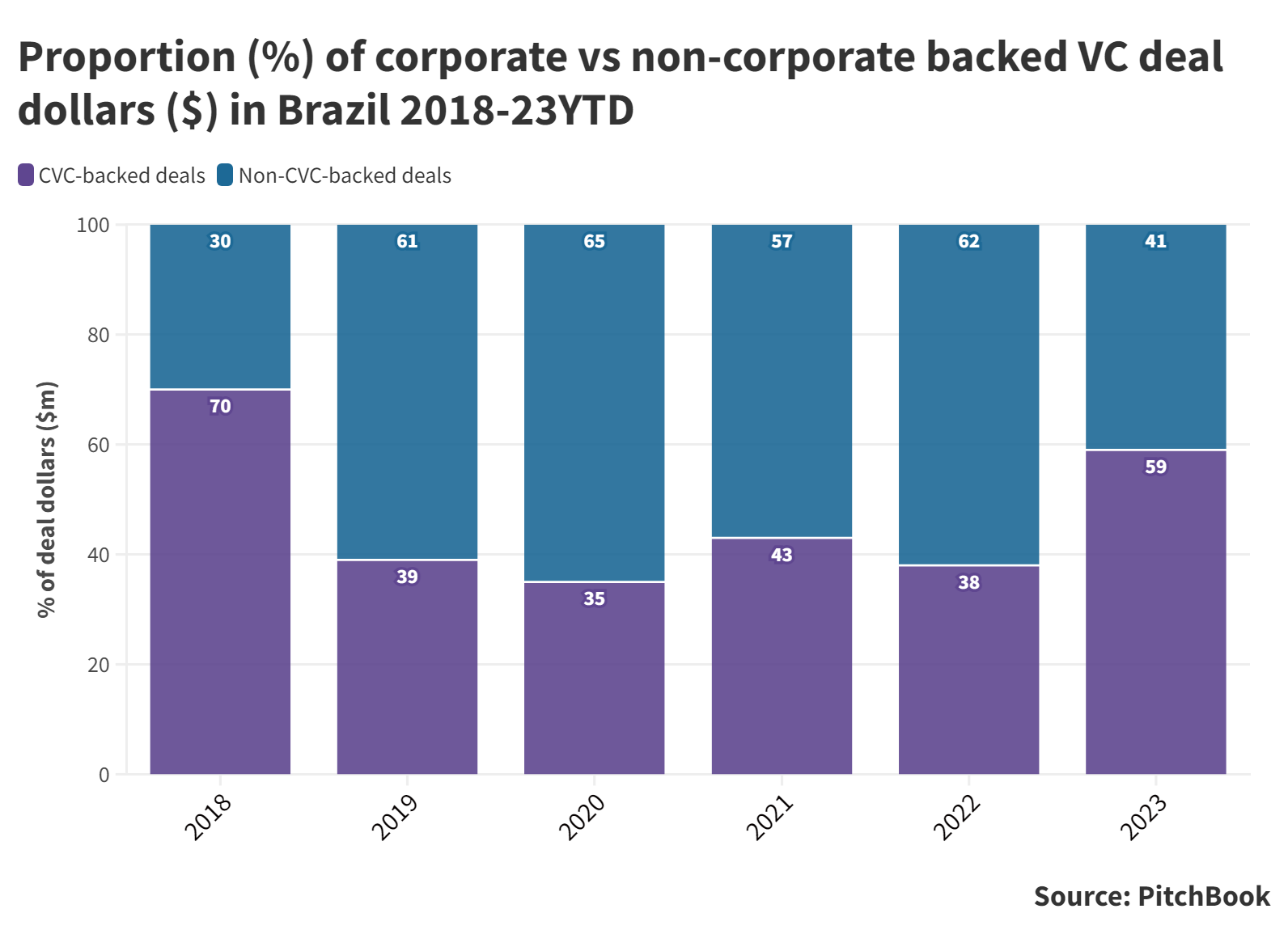

CVC-backed rounds represent 59% of the total investment volume in Brazil so far this year, despite corporations participating in far fewer deals. It marks the first time since 2018 that corporate-backed deals represented a larger portion than deals in which no corporates participated.

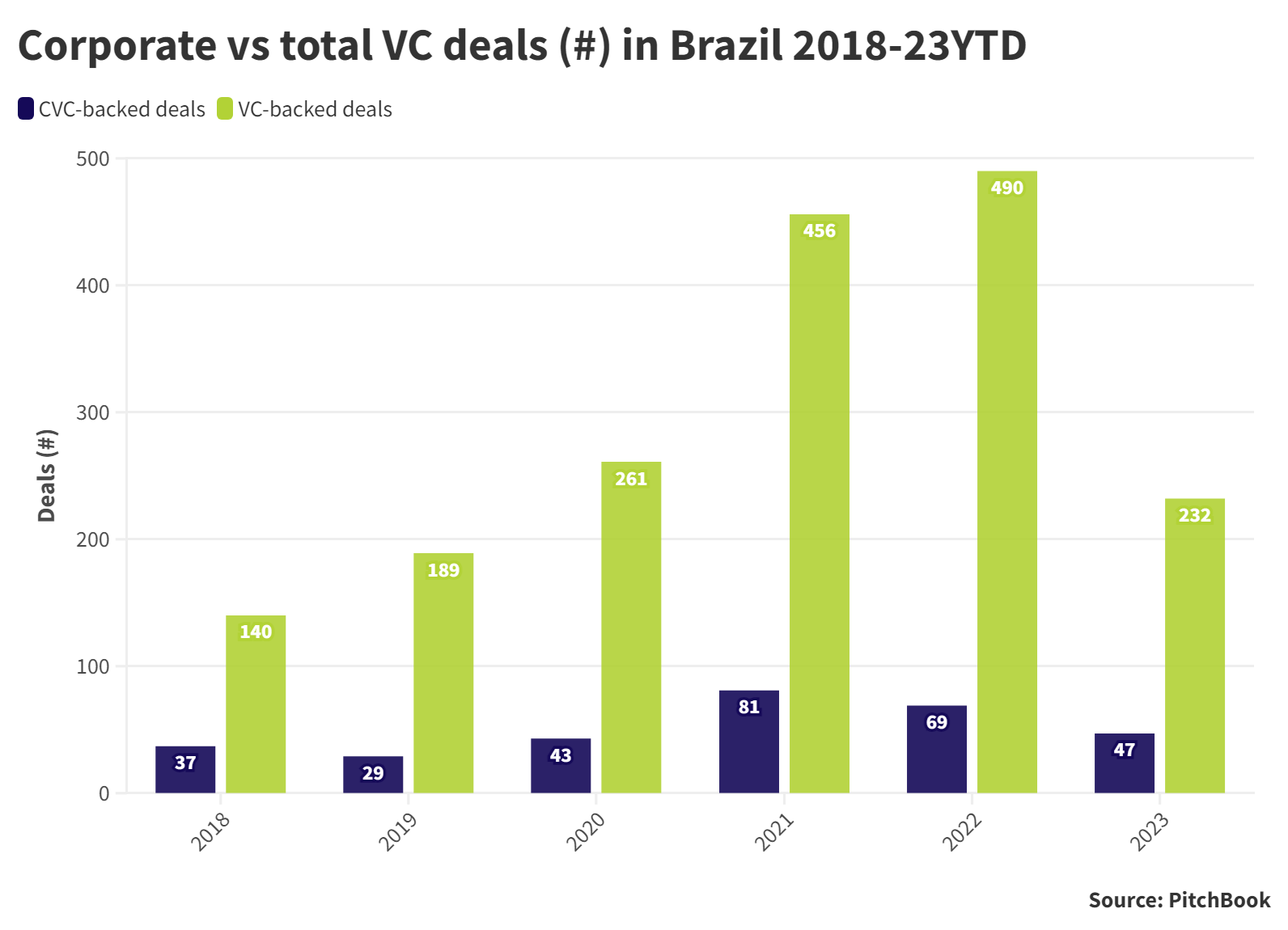

Looking at the past five years, we can see in the chart below that corporate-backed venture rounds in Brazil have generally lagged far behind the ones without corporate involvement, but they have been far more resilient in today’s market downturn – seeing far softer dents in the deal count compared to non-corporate backed deals.

The primary opportunity, not just in Brazil but in the wider LatAm region, is in inclusive technology rather than cutting-edge technology, according to Arthur Alves, corporate venture capital manager at Gerdau Next Ventures.

“When we see [LatAm] as a whole region, if it was a country it’s going to be like the third biggest economy in the world, only behind China and the US. When you compare it to some other emerging markets such as India, we’re going to have like one-third of their population, but at the same time we have double their GDP.”

This is partly why the biggest sector receiving CVC investment across the region is fintech – an area where the population tends to be underserved. The case of Nubank – the digital bank that went public in a $2.6bn New York IPO in late 2021 – highlights this dynamic.

Ecosystem building

One development that has accelerated many corporates’ entry into venturing has been the growth in the market for independent CVC fund managers, or CVC-as-a-service providers, that help ease corporates’ way into the sector.

Every month you open the newspaper and you see at least two or three new corporates announcing their CVC funds,

Richard Zeiger

MSW Capital was the first to begin back in 2000 – though back then it was more focused on consulting and education than on-the-ground investing – but has since been followed by many more. Valetec Capital, Vox Capital and Bertha Capital are just a few of the more prominent ones.

Third-party providers are also popular because in Brazil businesses need to be licensed by the financial markets regulator, the CMV, to manage a venture fund. This is a burdensome process for corporates which are just dipping their toe in the water. It tends to make more sense to just go to an experienced manager who is already accredited.

By a similar token, the rest of the supporting market infrastructure – the advisory roles like the lawyers, are also becoming increasingly professionalised and highly adept at figuring out compliance and risk reduction for corporates doing CVC.

“We’ve never seen such growth for the CVC market in general. Every month you open the newspaper and you see at least two or three new corporates announcing their CVC funds,” says Zeiger.

That is not to say that the “tourist” investors – who perhaps wanted to see their name in print and make a big splash with a big fundraise – weren’t around, trying to join the party.

“What I saw actually in 2022, in 2021, it’s just about the hype. ‘Oh, we have to do this corporate venture capital because everybody’s doing,’” says Alves.

“When I was working in a consulting firm, I saw it a lot: ‘Let’s do this corporate venture, let’s go to the news and just wait for the startups to come in and ask for money’. And that’s a terrible strategy, it never has worked.”

Ultimately, those don’t tend to do well. Without a proper commitment to invest in earnest, they quickly find that their progress plateaus.

Cassio Spina, lead partner at Alya Ventures and founder of one of Brazil’s first angel investor networks, Anjos do Brasil, says that the function of angel investment in Brazil has not changed much in the past decade, but their proliferation certainly has.

When he started in 2010, he recalls Googling angel investors in Brazil to little avail – there was some activity but mostly hidden from view. Today, they’re all over the place and are an important source of capital for the youngest startups.

I sat with one very good fund who said, ‘We have in our policy that we don’t co-invest with CVCs’.

Richard Zeiger

What’s more is that more and more corporate executives are increasingly making their own angel investments, which has made them more familiar with venture investing and opened up to the value that a CVC unit might be able to bring.

“They say to me, “This is my MBA for learning how to work in terms of innovation,’” he says.

A better image

A big hurdle that Brazilian CVCs still have to overcome is that of memory. The learning curve that they’ve gone through over the past several years has come with a lot of mistakes, and the resulting reputation they’ve collectively earned has proven hard to shake.

“Traditional VCs still have prejudice towards corporate VCs,” says Zeiger.

“Once I sat with one very good fund who said, ‘We have in our policy that we don’t co-invest with CVCs’. I started questioning the manager to ask why, and the answer was because corporates have been too predatory in the early days.”

Alves concurs: “Some corporate venture capital funds – they did deserve this kind of reputation.”

The situation has been less than ideal for corporates trying to get into a round, but what it did mean was an opportunity for corporate investors to position themselves as being founder-friendly and not predatory.

More recently, the negative perception has been waning. Although much of the time, CVCs are set up in the M&A structure – and for M&A ends – corporates are increasingly coming around to the view that these two functions, while potentially complementary at times, are completely separate functions. It is not uncommon today in Brazil to see corporate strategies shifting from M&A to CVC as a result.

It’s not just their reputation at the negotiating table that is proving a problem, though. There is also the perception that corporates, particularly the ones that may have some strategic alignment with the startup, would be potential buyers down the line, making founders and co-investors even more hesitant to allow them on the cap table.

International companies

While domestic units have been slower on the uptake, big international CVCs have been active in the country for much longer. The likes of Microsoft and Qualcomm have been investing in Brazilian startups for the better part of a decade.

“All of those companies already had their CVC arms, they knew at a certain point Brazil would be a place that would be not only hot, but mandatory, to do this.”

You have to look at the micro and understand your customer because the macro is going to change for sure.

Arthur Alves

The critical mass of foreign investors entering the Brazilian market, Zeiger says, has already happened. It is the homegrown ones – which may still be trepidatious about CVC or are still focused on other innovation tools like accelerators or hackathons – that now need to step up to the plate.

“I know that their innovation managers are dying to do CVC,” says Zeiger.

Geopolitical landscape

Given how constantly evolving the geopolitical climate can be in the region, Alves notes how it is not the macro environment but the micro environment that should command the most attention.

“That’s the game in our time. You have to look at the micro and understand your customer because the macro is going to change for sure.”

Another consequence of the political uncertainty is that some investors, like Gerdau Next Ventures, won’t invest in startups that have some relationship with the government, lest more risk be introduced to the portfolio.

Where the macro environment does have a big impact, however, is in the flow of capital for later-stage rounds. Large investors with their eye on emerging markets will be weighing Brazil and the rest of Latin America against potential investments in other regions like Asia Pacific, Africa and China. Early-stage investments in Brazil are a dime a dozen, and domestic investors have become good at making them – it’s the series Bs and Cs that are more scarce.

Around this time last year, Brazil’s presidential election saw the left-wing Lula government supplant that of right-wing Jair Bolsonaro, who was generally seen as very friendly to the private sector.

While the effect of the transition has yet to be acutely felt in the market, one way that may be manifesting itself is in a bill making its way through the Brazilian legislature that would change the taxation regime governing offshore structures – which the vast majority of fund managers use.

“I’ve heard a lot of noise about it. A lot – especially from tier-one funds in Brazil. Most of them, I’d say 80%, have their structures offshore. In the beginning of this industry, there wasn’t regulation for this in Brazil. [Offshore] was the same norm for private equity, for VC, for every type of fund,” says Zeiger.

Like many economies around the world, Brazil has been dealing with high inflation since the latter stages of the pandemic, and the consequently high interest rates are now proving a hurdle to investment, according to Spina.

That said, interest rates are starting to come down relatively steeply – with Brazil’s central bank surprising market observers with greater-than-expected rate cuts in recent months.

The relative lack of incentives for investing in startups – which would go a long way towards compensating for the high interest rates – could also be holding back domestic investors. There are tax breaks in place for investing in sectors like infrastructure or real estate, for example, but for investing in startups you can be taxed at the same level as fixed income.

Ultimately, however, all signs point to Brazil continuing on a strong path, outpacing the rest of the region while providing an increasingly reliable market for investors from regional neighbours to invest in.