Oil and gas corporations continued to deals at the same pace in the second quarter, but the total estimated dollar valuation of those deals show a sharp drop.

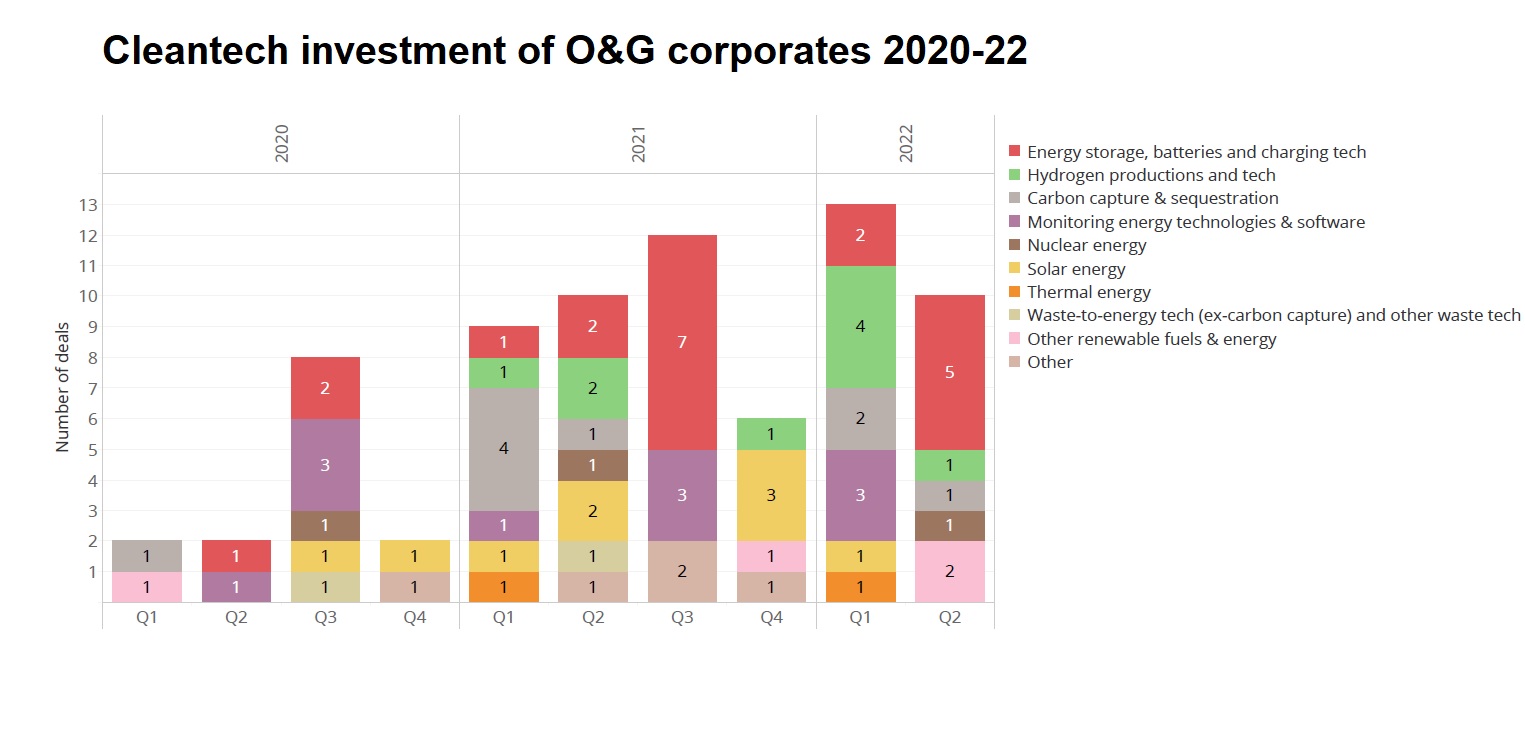

Cleantech deals are the only exception — as the sector reacts to a need to decarbonise, deals have remained at high average values.

We also saw fewer exits than in previous quarters and more personnel moves in relevant venture peers in the energy sector.

All the while, the macroeconomic climate for the commodity prices driving the sector remains favourable.

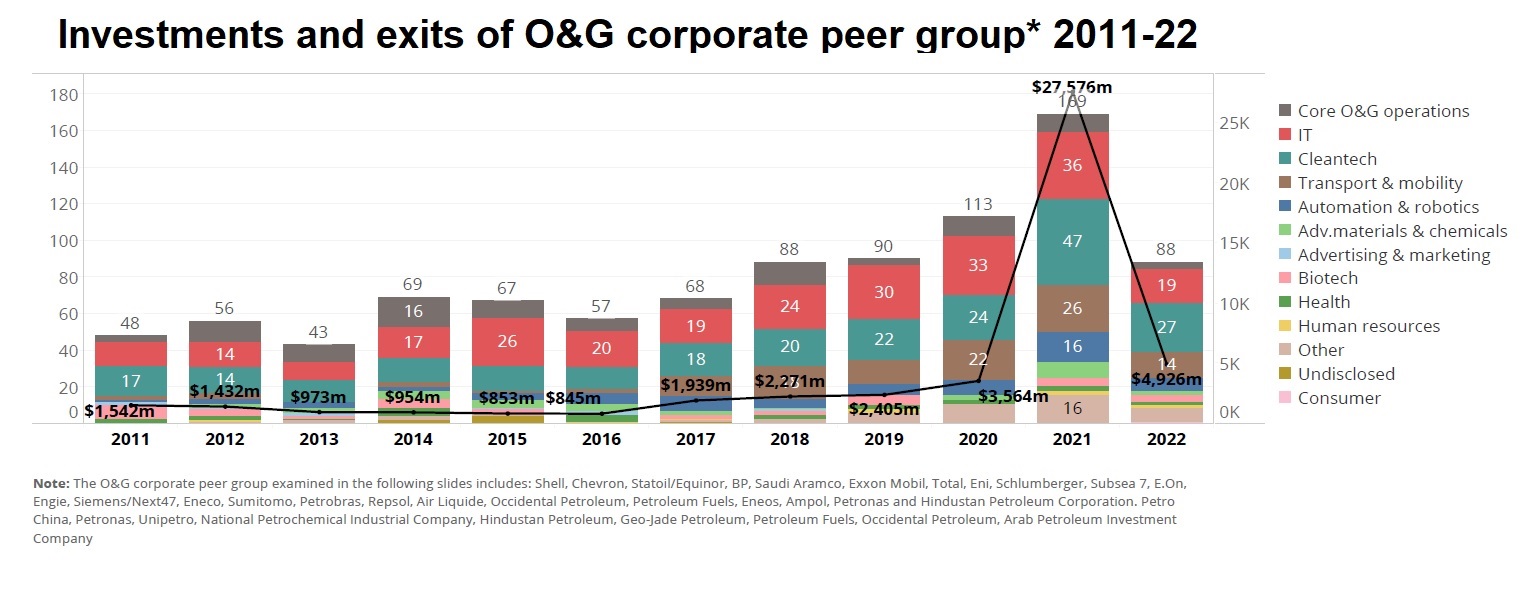

Figures from the first half of this year show 88 transactions involving a corporate investor in the oil and gas sector, which would put the sector on track to reach a similar number of deals as in 2021, when there was a total of 169 transactions in the full year.

However, the total valuation of those 88 deals is just $4.93bn, a fraction of the $27.58bn bumper deal value of 2021, when a flood of liquidity and accommodative monetary policy helped lift valuations in buoyant public and M&A markets.

The areas where deal sizes have remained the most robust are cleantech, IT and transport. The average size of deals in sectors in which oil and gas corporate venturing peers participated, stood at $69.34m in 2022 so far, slightly higher than the average in 2021 ($65.84m) –both of these a surge from previous years.

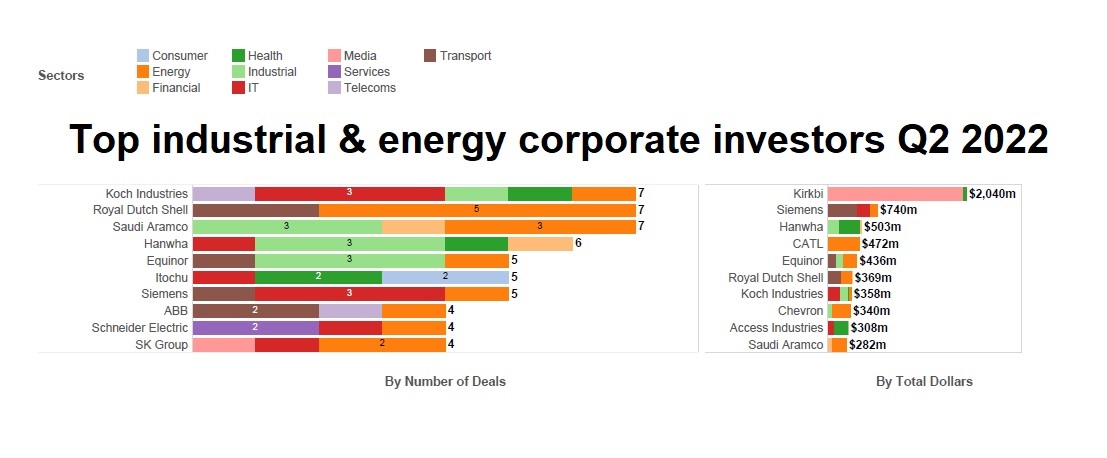

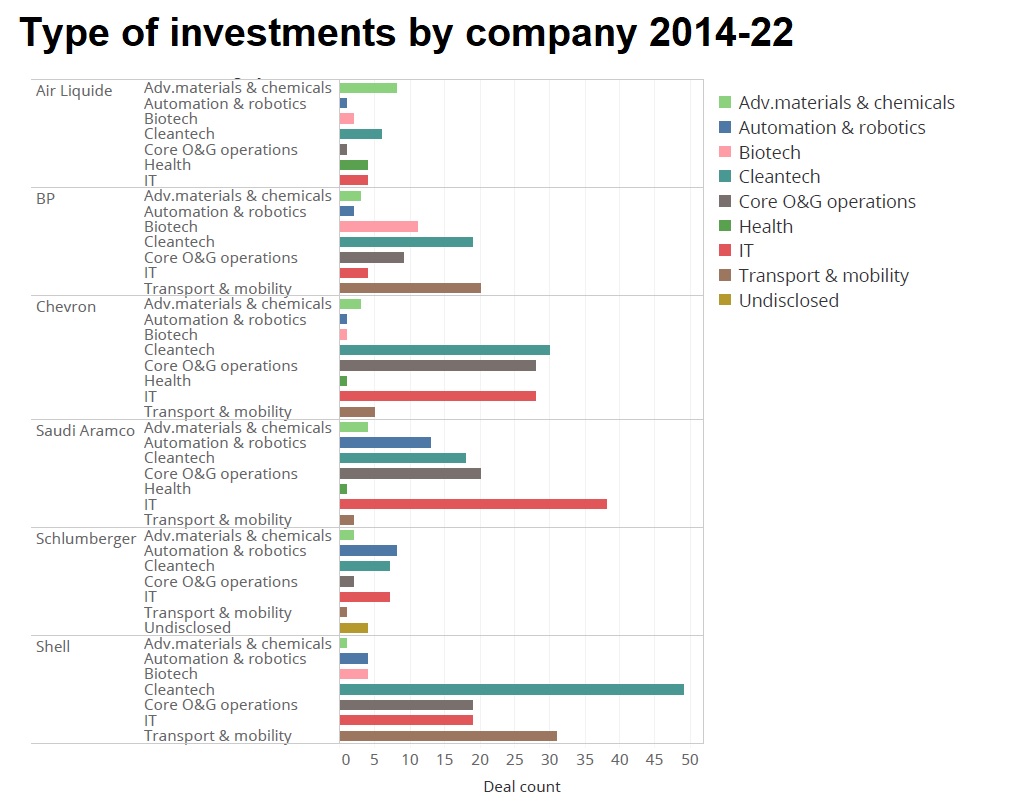

Chevron and Saudi Aramco have been leading the charge, with investments in cleantech and IT since 2014, while BP and Shell have most investments in transport startups in this peer group.

Energy storage powers on

In terms of subcategories, batteries and energy storage, as well as hydrogen-related technologies have been some of themost popular investments so far in 2022.

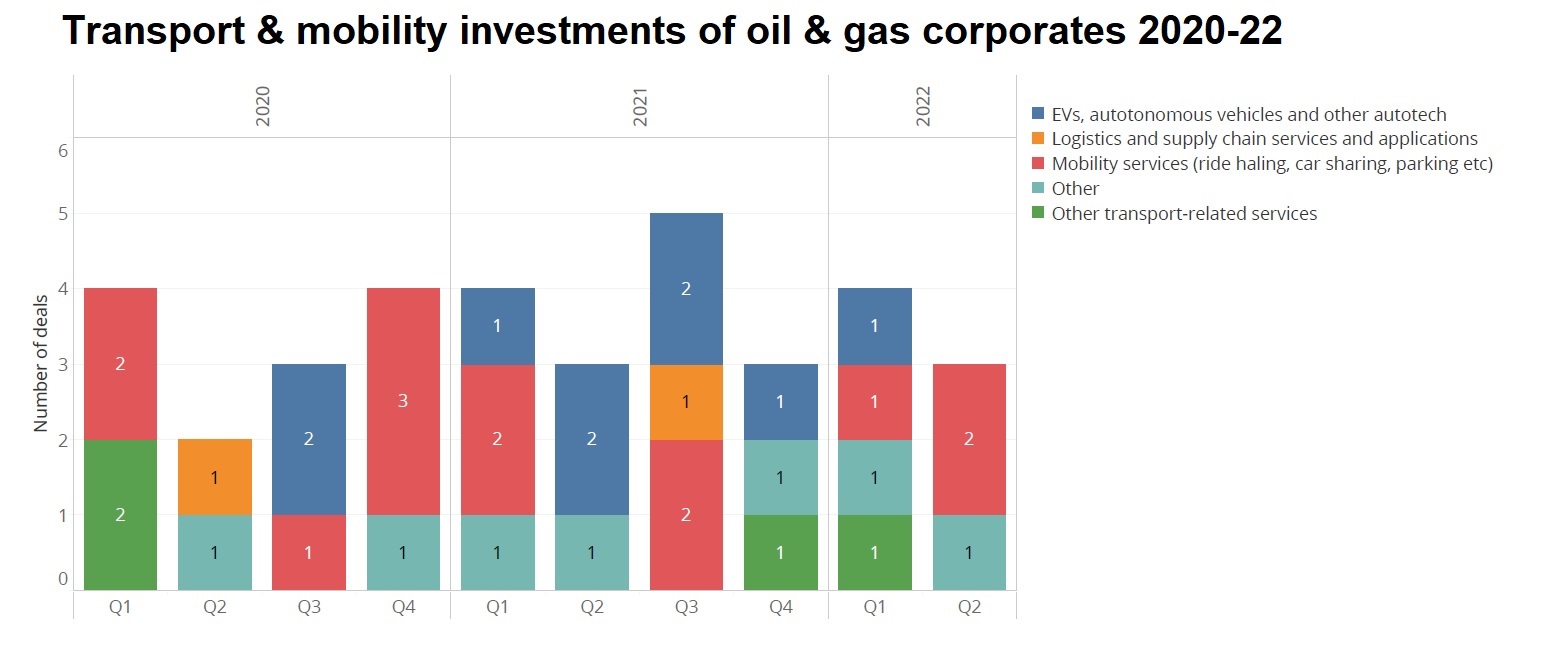

As for the transport and mobility space, autotech (including electric vehicles and autonomous vehicles), as well as various mobility-related services are the most popular subcategories.

The steady investments from oil and gas majors comes despite a turbulent few years. Just two years ago, during the second quarter of 2020, when the first wave of the covid-19 pandemic was in full swing and global stay-at-home orders were imposed, pressures on both the demand and supply side made the oil price fall to less than $20 per barrel, down from $50-$60 in previous months. WTI futures even entered negative territory in April for technical reasons, which made for memorable headlines.

Since then, oil prices have moved up considerably and appear likely to sustain their levels in the short run, given the overall supply situation. By the end of the second quarter of 2022, WTI was trading just above $100 per barrel, having corrected down from levels around $120 per barrel. Analysts from investment banks have set wildly different price targets for crude –ranging from the most optimistic from JP Morgan ($380 in one scenario) to the gloomiest from Citi, setting it at $65 per barrel –a collapse from current levels due to a potential recessionary drop in demand by year end.

One independent source of forecasts is the US Energy Information Agency’s Short Term Energy Outlook report from June 2022, according to which there is likely to be a tight market, which means the price of crude will probably remain around the $100 mark in the short run.

Pressure mounts on gas

Most recently, we have also seen mounting pressure on the price of natural gas, particularly with respect to Europe. Currently, the price of natural gas stands at around $6, having reached a high of $9.322 (at the time of writing), up from around $3.60 in January this year.

The gas situation is particularly acute in Europe, as the continent has relied heavily on natural gas for heating, as well as for its electricity generation. Coal power plants have been largely replaced with alternative renewable sources. However, this process would be unthinkable without using natural gas to supplement renewables when necessary.

More to the point, in early July 2022, the European Parliament backed European Union (EU) rules labelling investments in gas and nuclear power plants as climate-friendly.According to data from the International Energy Agency, a significant part of the natural gas supplies for Europe originate from Russia, which further complicates matters, given the ongoing conflict in Ukraine.

In 2021, the EU imported 155 billion cubic metres of natural gas from Russia, accounting for around 45% of total gas imports and close to 40% of its total gas consumption. Europe is currently actively seeking to diversify its gas suppliers and the short-term effects of this are likely to be painful. France’s new prime minister Élisabeth Borne announced the intention to renationalise the country’s indebted electricity utility EDF in a push to tackle the energy crisis aggravated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

In Germany, utilities EnBW Energie Baden-Wuerttemberg and RWE have been reported to have contingency plans to turn to its coal plants, as Russia cuts gas supplies through Nord Stream, which could thwart refilling of inventories in time for winter.

Cracks spread wide

While electricity is an input cost of nearly everything and is likely to hit producers before costs get fully shifted onto consumers, there is also the question of gasoline prices, which are hitting everyone’s pockets directly.

Gasoline prices are formed in a very particular way, where they depend on a multiplicity of factors that go beyond merely the input cost of crude petroleum. Depending on where in the world gasoline is produced through refining, one of the big factors is the US dollar exchange rate vis-à-vis the local currency, as crude is traded internationally in US dollars.

Then, an important measure to look at is the so-called “crack spread”, which is the difference between the purchase price of crude oil and the selling price of its finished products –gasoline and distillate fuel. Put simply, that difference captures the additional costs and inputs and profit margins for refiners.

Since the beginning of 2021, the crack spread in the US has spiked and this is due to the lack of sufficient refining capacity to meet current demand. All these developments are, generally speaking, very bullish and favourable indicators for the oil and gas space. In the meantime, oil and gas majors and their peers have remained active in the corporate venturing arena, irrespective of headwinds or tailwinds.

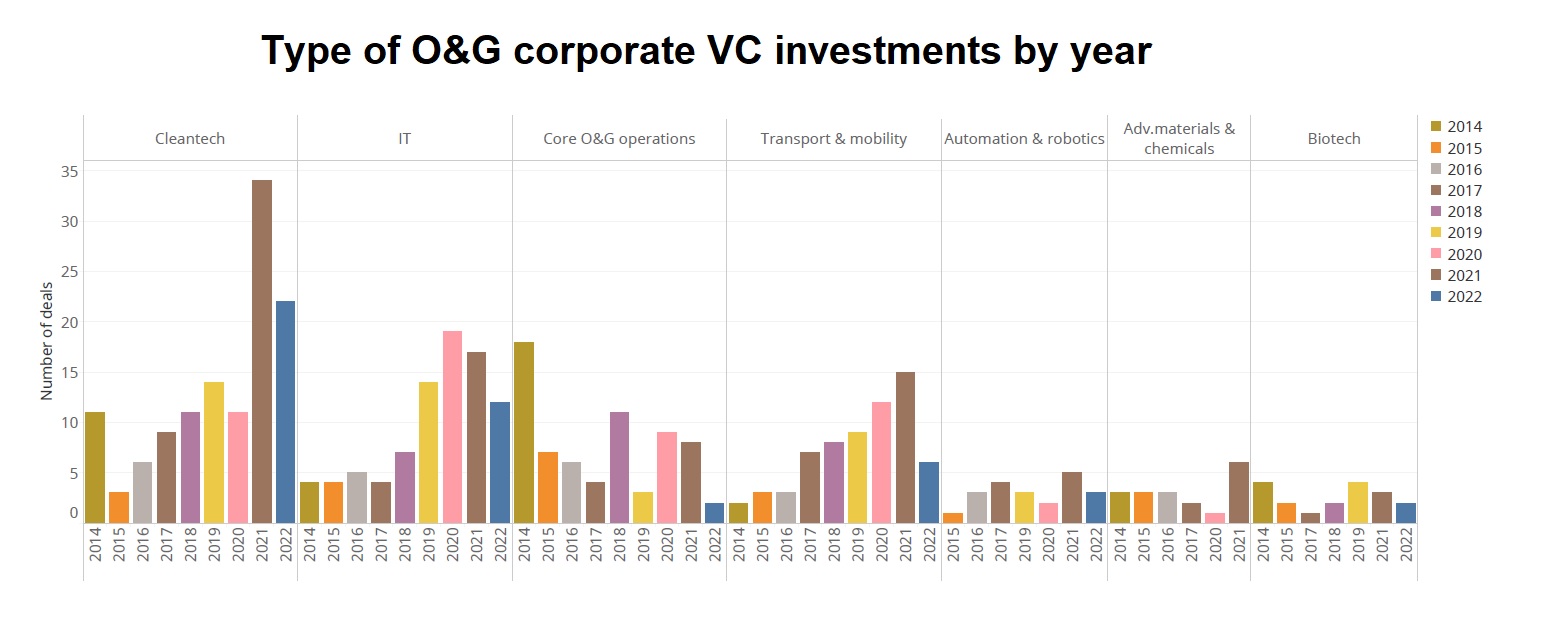

During the latter half of the past decade, we have observed a shift in focus among them, still evident today and likely to continue to hold in the post-pandemic world. Many of the disclosed deals by such corporate venturers are going into emerging businesses from non-core areas, primarily into IT and cleantech, as well as transport and mobility. Such non-core areas are precisely those considered to have most disruptive potential to the core business of oil and gas companies, as low-carbon energy technologies may reduce or ultimately replace the fossil fuels’ position in the future.

The increasing adoption of electric vehicles may affect a considerable part of the customer base of oil and gas companies, though how quickly or slowly this may occur is debatable. On the other hand, there has also been a growing digitisation of industrial activities, which exerts a tangible impact on production and efficiency.

Investing in solutions

Despite this focus elsewhere, it would not be unreasonable to expect more investments in core oil and gas technologies, particularly in companies whose solutions provide significant cost-savings or make operations less contaminating. Such investments will continue to form part of the portfolios of corporate venturers from the sector due to its capital-intensive nature, contingent on the up and down swings of commodity prices. Thus, any innovation improving processes and reducing fixed costs are likely to be embraced. This holds true in a time of rising prices of oil and gas and limited refining capacity.

So far in 2022, we have seen relatively fewer deals (at least among the publicised and disclosed ones) in core oil and gas applications, but this may change by year end.

In the long run, corporate venturing arms of oil and gas incumbents will likely continue to have more strategic rather than purely financial orientation. In addition to investing in technologies that may profoundly disrupt the sector, strategic benefits may come in the form of building an ecosystem, finding suppliers or helping business units with specific technical challenges.