Whether or not to forego potential investment from an investor linked or tied to a hostile state is an issue of increased importance to all startups but especially for those with so-called dual purpose technologies – ones that can be used for civil and military purposes.

It probably helps if you are the third-best funded startup in a sector of critical potential national importance, but Christian Weedbrook, CEO of Xanadu, a Canadian quantum photonics company, says its decision to avoid autocratic state investment had not held it back so far. Weedbrook made the comment during this week’s Canadian deep-tech startup showcase hosted by the embassy of Canada in Washington DC, in partnership with the Business Development Bank of Canada and Global Corporate Venturing (GCV),

Xanadu recently achieved quantum computational advantage, which means its technology can perform some calculations far faster and with lower power requirements than traditional binary computers using ones and zeros. It has raised $275m from investors including the Business Development Bank of Canada and corporations such as Volkswagen.

Quantum computing has the potential to crack traditional cryptography that underpins most cybersecurity measures, creating threats to national security.

The sweep of technologies affected by US and other government restrictions is also increasing.

European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen this week said the European Union needed to ensure that its companies’ capital, expertise and knowledge were not used to enhance the military and intelligence capabilities of the bloc’s “systemic rivals” — of which China is one, according to the Financial Times (FT).

The commission is examining the creation of a mechanism for scrutinising overseas investment by EU companies in an undisclosed number of sensitive technologies that could enhance the military capabilities of rivals, she added before her trip to China next week.

But, as funding for startups continues to fall this year, the pressure on CEOs to trade off potential security risks against the competitive need to raise capital will likely grow. Working out whether your tech will be caught by state restrictions could prove crucial.

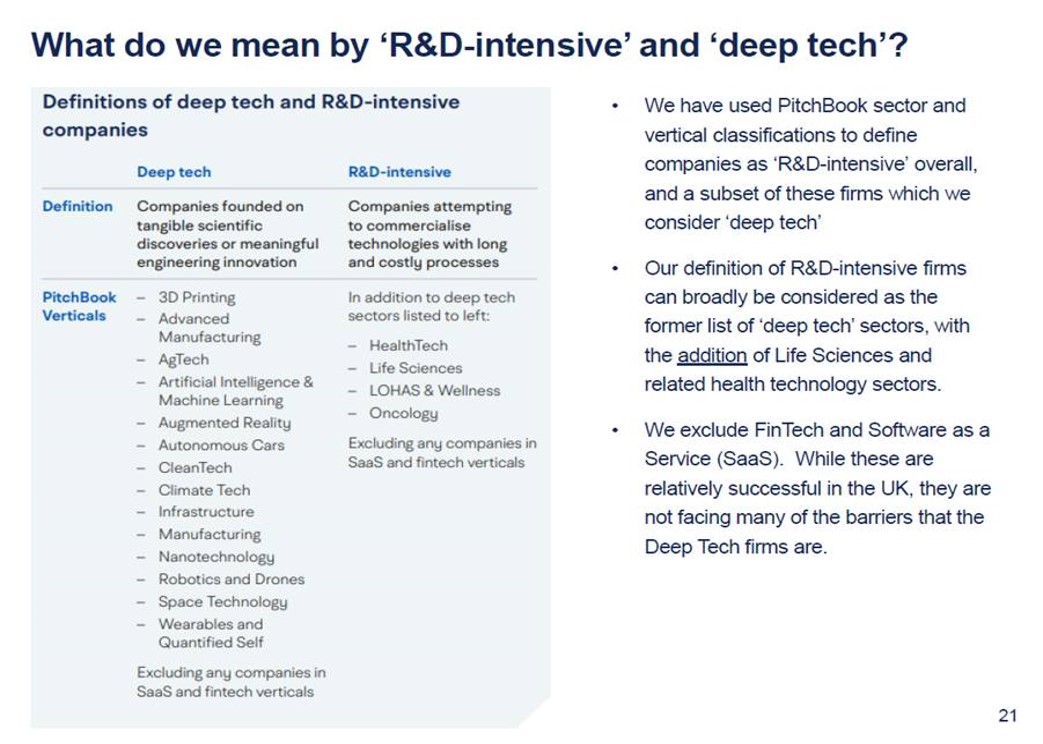

The graphic below lists the traditional deep tech areas as defined by data provider Pitchbook, while governments, such as the UK, can look more broadly at what they call research and development (R&D) intensive ones, which often means adding in health and life sciences.

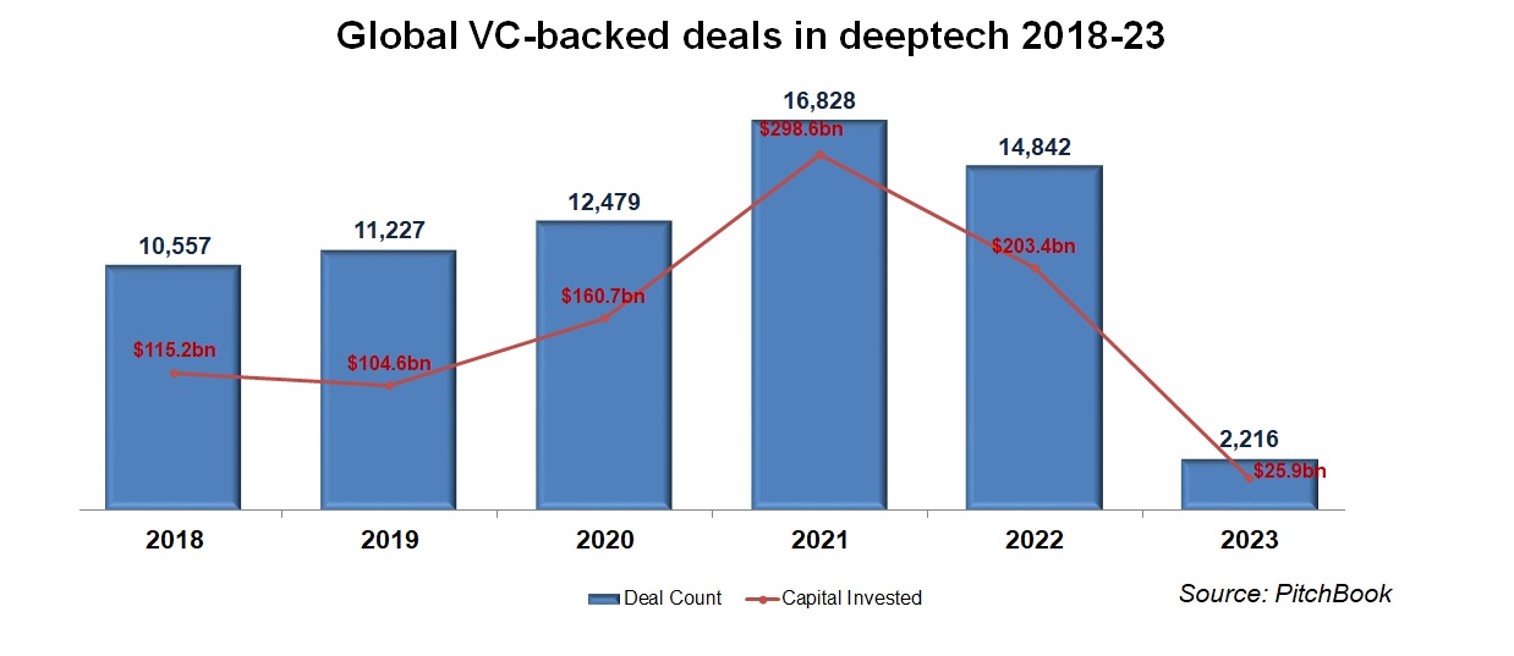

Last year, VC investment in deep tech held up from the highs of 2021. Compared to a 25% drop in overall VC deal volume last year, deep tech was down by just more than a tenth to almost 15,000 deals, although by deal volume the fall was nearly a third.

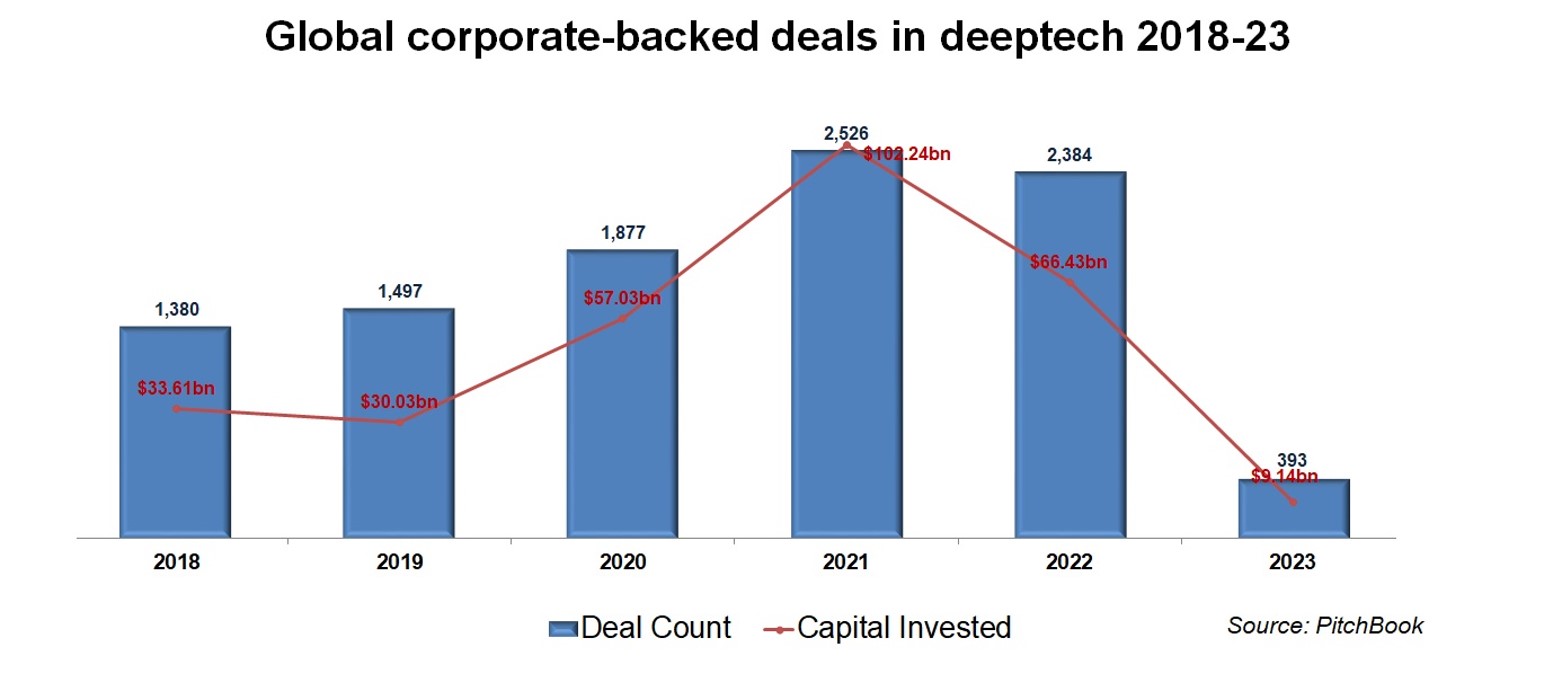

Corporations mirrored this relative resiliency, Pitchbook added.

But this year the impact on deep tech is expected to grow more severe. In the first quarter, activity has fallen to its lowest total in the past five years.

This will put more pressure on governments. Michael Jackson, a VC, noted in his blog: “Belgium’s intelligence service is scrutinizing the operations of technology giant Huawei as fears of Chinese espionage grow around the EU and NATO headquarters in Brussels.

“There’s a lot of Chinese money in European deeptech, including from Huawei. It’s a serious subject that should get a lot more attention than it does. Fwiw [for what it’s worth], the Belgians should also be looking around Leuven (and the Brits in Cambridge and Oxford, the Dutch in Eindhoven, and so on).”

To help foster collaboration between #corporate investors seeking to invest in this area, GCV has launched the Global Defence Council for strategic investors, co-chaired by Thomas Park, partner at the Business Development Bank of Canada Deep Tech Fund, and Ryan Lewis, partner at SRI Ventures. Hear editor Maija Palmer talk to Lewis and Park about why they are setting up the GCV Defence Council Advisory Board.