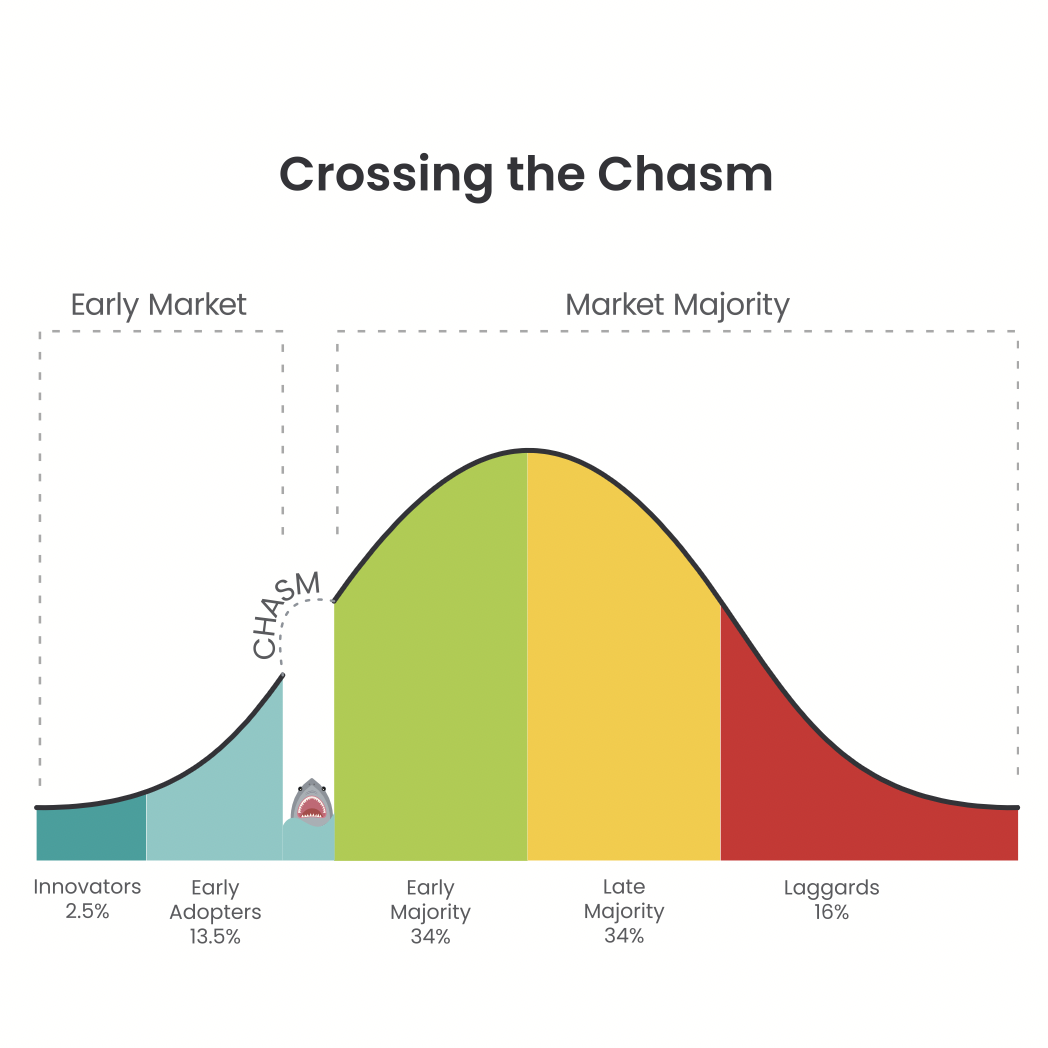

First published in 1991, Geoffrey A. Moore’s book “Crossing the Chasm” examines market dynamics faced by innovative new products. There’s a vast chasm between early adopters and the early majority. Early adopters are willing to accept imperfections for the advantage of being the first, but the early majority have much higher expectations.

It was mostly applicable to IT companies back then, but it’s still relevant to many innovation-driven startups today trying to close the gap between early adopters and the early majority.

The same chasm model applies to many of the material-based startups we work with or have met. These startups, too, need to cross the chasm to reach the inflection point where they achieve market relevance.

Over the years, we’ve spoken to and evaluated over 3,000 materials startups from around the world, and here are three types of chasms that we’ve seen most often with materials startups.

1. The cost chasm

Nearly hardware innovation struggles with this. It’s very hard to scale a product if producing it is expensive. The product may end up as a showcase project invested or bought into by visionaries or companies that can afford them, but generally, expensive innovative products will find it hard to land commercial early adopters. This is a cost chasm. Here are two examples:

Smart Windows

Remember electrochromic windows? They work like magic, turning glass opaque or transparent at the flick of a switch. It’s been around for years, yet it’s not widely used or applied. Even today, the cost of purchasing and installing these windows remains very high. Installation is very complex as the edges must be sealed properly with the wiring in place – and if more windows need to be installed, the cost grows exponentially. You might come across them in trophy office developments, or perhaps, highly secretive HQs.

‘View’ (NASDAQ : VIEW) — a leader in the smart glass tech — was founded in 2007 and raised $1.8bn. It went public in 2021 at $2B valuation. In May 2022, the company announced that it didn’t have enough cash to meet its financial obligations for the next twelve months. The market cap has now dropped to less than $200m. An analyst estimated that: “View must be applied in at least 1,900 commercial construction projects per year to earn $1 bn in revenues.”

Biofuels/Sustainable Cosmetics

Several synthetic biotech companies are boldly trying to deliver breakthroughs such as biofuel or sustainable cosmetics. The concepts are fantastic, but the costs behind its science and production can be prohibitive. “The feedstock inputs you need for biodiesel are more expensive than petroleum,” Jones Prather, chemical engineering professor at MIT said. “On top of that, the processes for producing the fuel aren’t yet efficient enough so that you can produce it very cheaply.”

Companies, such as Amyris (NASDAQ: AMRS), the world’s leading manufacturer of sustainable ingredients made with synthetic biology, must deal with very high costs of research and production. Amyris started nearly two decades ago, but is still struggling to reach cashflow positive status today. Like View, its stock has lost over 90% of its value since its public debut in 2020.

2. The scalability chasm

It’s the question of supply trying to meet demand. Sometimes startups need to be able to deliver massive capacity to support the scale of the industry’s expectations. There are two strong examples of this:

The solar energy industry

The numbers are staggering. Solar farms take up massive swathes of land and require huge numbers of solar cells. One acre might require as many as 2,000 . Conservatively, it takes 10 acres to produce just 1 megawatt (MW) of electricity. The solar energy industry is mature and massive, where trying to even achieve a 1% improvement in efficiency is remarkably difficult. The cost squeeze is down to 1/10th of a penny. There is almost no way for startups to know if they’re able to scale to massive demands on such a tight cost window.

The energy storage industry

This includes technologies such as batteries. All downstream customers tend to be large-scale, wanting to adopt new advances in battery technology as long as they can be guaranteed a stable supply. Again, the numbers can be staggering: for example, a single electric car needs an average of 7,000 individual cells. If an average electric car manufacturer produces 365,000 cars a year, that’s 2.5 bn cells needed in a year. If startups in this space are unable to raise enough financing, having insufficient scale will mean this chasm cannot be crossed.

3. The value chain/time chasm

For startups positioned upstream in the value chain, offering partially completed products or solutions to customers, our experience indicates it can take 18 to 24 months to validate the product with each step on the value chain. In total, it can be 8-10 years before the company can see actual product adoption and commercial revenue. Before that time, these startups will have to rely on a variety of VC financing, grants and joint development agreements (JDAs) that trickle in — and the reality is that many of them do not survive.

Examples of companies facing this chasm include semiconductor material companies, as well as new materials that go into consumer electronics.

Identifying the chasm that a startup will face is of critical importance, because this will help the company plan their next move to achieve their goals. Which begs the question: what should founders of innovative material companies do about the chasms?

For startups:

1. Know your chasm

Once you understand the type of chasm you’re about to tackle, you can plan to deal with it head-on. Be sure you have a good strategy or you will end up down an unrewarding path. Let’s look at the electrochromic window industry again: inventing a better electrochromic window that switches even faster isn’t going to be the ‘killer’ solution for this class of technology. Remember, the issue is cost. If you can kill the cost, you’ll close the chasm. A 10X reduction in manufacturing cost for electrochromic windows is a good breakthrough because it makes it much more accessible. But since installation of smart windows is very complex and expensive, targeting a 50X reduction in installation cost might just be the ‘killer’ breakthrough to change destinies.

2: Have the right partner for the type of chasm you are going to face

It’s important to have the right partner by your side from day one to help you to cross the chasm. If you are facing a scale chasm, you might need a manufacturing partner that can help scale up your technology with their existing facilities. For value chain chasms, you can partner with the OEM (brand owner) to get the OEM interested in pulling the value chain along.

3: Don’t rush financing (very important)

It’s best to delay any kind of VC financing until you’re ready to cross the chasm or at least have a strategy in place to cross the chasm. Crossing the chasm is more about whether you have the right technology, solution, cost and customer combo in place. VC money can help you with recruiting and operations but it won’t solve the issue if you’re addressing the wrong problem, or if you’re waiting for the value chain to react one step at a time. Unless you’re a star-power entrepreneur with talent to raise massive capital, that isn’t going to help with ‘scale’ chasm either. Delaying VC fundraising until you have a clear path to the other side of the chasm also means you get to retain more equity in the company, giving you the opportunity to build up the company faster in the long run.

For VCs

While it’s challenging for materials startups to cross their chasms, VCs investing in this space also need to know their own chasms, and what it takes for certain technologies and industries to succeed. Here are 3 considerations for VCs.

1. Know what kind of chasm startups in certain technology areas and industries will face

Know which chasm a certain type of company is likely to face, and don’t fund a company without a strategy for crossing it. Don’t fund it too early, either — timing is key. To help the portfolio company grow, the VC has a responsibility to nurture the startup, understand its challenges, and help it cross the chasm it faces. Don’t get too distracted by the response of the early adopters. And remember, it’s hard to scale up early trophy companies.

2. Make sure the startup can tackle its own chasm

Can the startup deal with its own chasm? Many VCs tend to be attracted to startups with great concepts but may forget to consider certain realities. JDAs are a way to work through it, but JDAs with bigger firms can take up to 3-5 years to materialise – and smaller startups simply can’t wait. It’s best to make sure your portfolio companies can cross the chasm on their own. You can always work out a strategy with them to achieve their objectives.

3. The startup must have sufficient funding

Be very sure to provide enough funding for your portfolio company. An under-funded startup will inevitably have to ask for bridge loans — and bridge loan after bridge loan won’t help the case. The startup needs to be able to stand on its own two feet from the get-go. On top of financing, investing your time and partnership are crucial elements to help it step up.

But of course, there’s nothing better than a wealth of industry experience and scientific understanding of the technology you’re investing in. As materials are instrumental in many industries, time-accumulated knowledge, and experience from looking at thousands of companies is the only way to recognise the chasms and what it takes to cross each chasm. At CM Venture Capital, we’ve been investing in the materials space over the last decade. We’ve evaluated over 3,000 innovative materials companies, but we’ve funded less than 1% of them, as hardtech is not an easy space for startups to succeed.

Written and researched by CM Venture Capital’s investment team, a China-headquartered investment company which partners with a number of multinationals to help them invest in cutting-edge hardtech.