“If you have always done it that way, it is probably wrong” – Charles Kettering

Today there is an excess of capital in the VC markets that include corporations who are actively participating in VC investments. It is easy to identify technology companies that through their funds such as GV (formerly Google Ventures) Coinbase Ventures, Salesforce Ventures, seek not only a financial return but mainly innovation, disruptive technologies and new business models that support their strategy.

In the first half of 2021 alone, the corporate VC funds (CVC) have invested more than $78bn in 2,099 transactions, which represented an increase of 133% in terms of capital and 27% in terms of the number of transactions compared to the same period of the previous year (CBInisights). It is estimated that globally there are more than 4,000 CVC funds, which represents an increase of 6.5x between 2010 and 2020 (The State of CVC, 2021).

Despite all this enthusiasm, does a corporate really need to invest directly in VC to generate innovation? What type of corporate is required to use this investment strategy?

Before answering these questions, it is relevant to remember that the flow of capital to VC increased substantially in the late 1970s and early 1980s since in 1979 there was a change to the “Prudent Man” rule that governs investments in pension funds. This allowed fund managers to invest in high-risk assets including VC. Similarly, in the 1990s, an important flow of capital from corporations also served as investment in technology-based companies. This has led to the main companies in the US stock market by market capitalisation being technology companies such as Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, Google and Facebook with a much shorter lifespan than the companies that dominated the stock market 20 years ago.

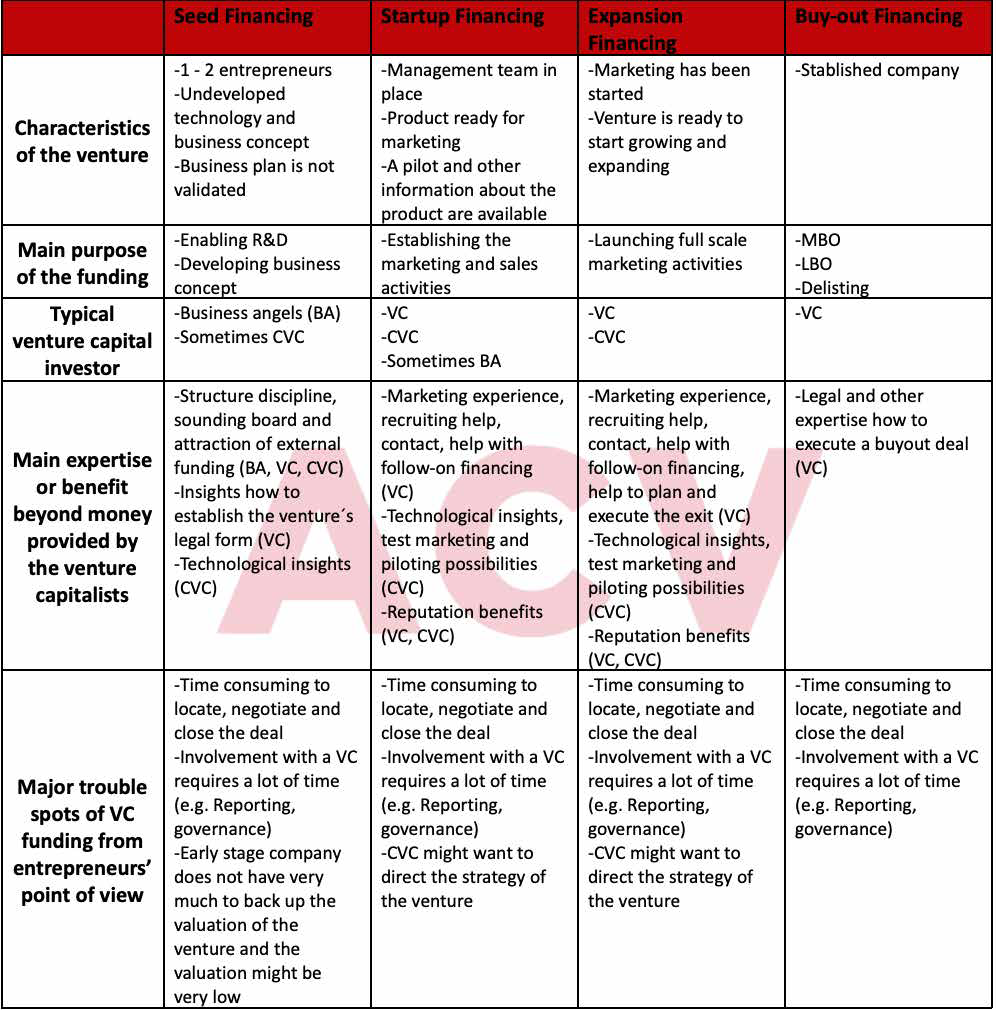

CVCs’ investments are usually minority investments in the capital of firms established in entrepreneurship projects or startups. These investments accompany the corporate venturing strategy of the company that has other tools such as corporate builders, accelerators or M&A to accelerate innovation within the organisation.

Additionally, companies view CVC activity as an early warning system and use it to evaluate novel entrepreneurship inventions that could be used by the organisation.

In general, companies tend to invest in new ventures in industries with high technological generation, limited intellectual protection and with complementary distribution capacities. Furthermore, the more cash flow generation and absorption capacities the organisation has, the more likely it is to invest in VC (Dushnitsky and Lenox).

Traditional organisations are often slow, bureaucratic, and outdated. Startups can be a high-value source for generating innovative ideas. However, to extract value, organisations require a 360-degree change in their leadership and culture, otherwise this practice becomes unsuccessful or very slow to add real value.

Organisations that are investing through a CVC truly recognize that highly skilled human capital becomes more important in generating value than physical capital or administrative personnel who have been in an organisation for more than 30 years without experiencing dramatic change of innovation in the markets. For this reason, investment in VC becomes an access to a portfolio of scientists and entrepreneurs who could hardly be hired by the company.

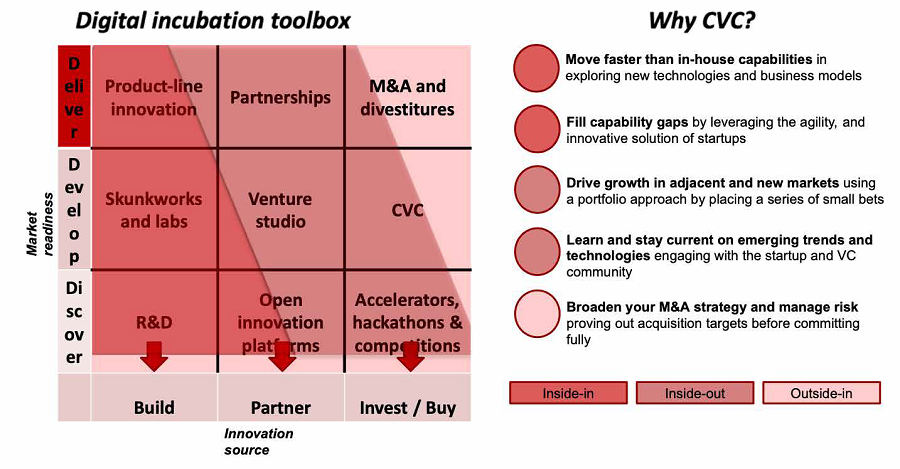

Before defining whether a company is going to launch its own CVC, it really needs to understand what it is looking for when carrying out this activity and what complementary tools of Corporate Venturing are not a better source of value generation and innovation.

The typical responses of a corporate are:

• Innovation: To improve products and services, processes and even business models; for example, cable TV vs streaming platforms

• Fill gaps: In their organisational capacities that allow them to cope with market changes; for example, direct distribution to consumers with their own fleet or using the gig economy

• Boost growth in new markets: Accelerate the organisation’s growth thesis; for example, traditional commerce vs e-commerce

• Move faster than only with its internal capacities: Seek the generation, implementation, execution and strategies and projects strengthening the organisation; for example, traditional banking vs neo-banks

• Learn and be aware of emerging trends in technology, innovation and business: Traditional organisations lose sight of the long term by focusing on quarterly reports to their shareholders and the public markets

• Increase its M&A strategy: Companies like Google, Facebook, Goldman Sachs are a benchmark in acquiring innovation through purchases

Companies that invest in VC generally use one of two models:

• In-house: Internalized team that carries out VC activities. It usually operates as an internal area of the organisation, which makes it difficult and lengthens the decision-making process when investing. You can have an established capital commitment or make ad-hoc investments

• Outsourced: Investments through an independent team that can be dedicated or can have multiple corporations as LPs. Retains the agility and structural discipline that an independent VC fund has

Sometimes companies enter de CVC business by wrong copying or looking for simple solutions without having an idea of what they are doing. The main funds in the ecosystem take into consideration these elements:

• Speed and agility: Eliminating bureaucracy, facilitating decision-making and promoting empowerment are essential.

• Financial and strategic returns: Have a long-term vision measuring results and seeking added value to the organisation’s strategy.

• Compensation: Adequately incentivise CVC members with structures that equate to an independent VC fund.

• Professional development: VC activity is a profession itself that requires knowledge, experience and networks to be able to develop at the highest level and it is not a position as other where people can be rotating within the organisation.

• Knowledge and expertise: To be a competitive CVC in international markets, it is necessary to adapt the best market practices and have an experienced team.

• Conflicts of interest: Without an experienced and independent team, organisations promote transactions that do not make sense and also lead to confrontations of power and politics within the organisation and with the entrepreneurs and other VC funds.

• Capital markets: Do not pay a premium to the valuation of companies for having a CVC.

• Visibility in innovation and trends: Organisations do not need to invest to be able to have this experience, there are other tools that provide innovation within the organisation.

The search for innovation is something that is in the sight of most companies with a long-term vision. However, you do not need to invest in VC to access disruptive businesses, technologies and innovation.

Companies should learn from Google to establish their Corporate Venturing strategy seeking innovation through multiple channels. Additionally, companies should fully understand CVCs’ best practices if they decide to employ this strategy to perform well and truly create value.

“Innovation has nothing to do with how many dollars you have. When Apple came up with the Mac, IBM was spending at least 100 times more on R&D. It is not about money. It is about the people you have, how you are led, and how much you get it.” – Steve Jobs

First published in AC Ventures’ monthly newsletter.