Since the beginning of the covid-19 pandemic, there has been quite a turnaround in the oil and gas industry, or at least in the prices of the underlying commodities that dictate its development.

In March 2020, when the pandemic engulfed the western world and stay-at-home orders were imposed, pressures on both the demand and supply side had made the oil price go down to less than $20 per barrel. WTI futures even entered negative territory in April, which made for some very memorable headlines, though this was partially due to a technicality related to the physical delivery settlement of such contracts. On the last day of 2021, oil prices stood at around $75 per barrel (WTI) and $77 per barrel (Brent), having been extremely volatile during the period.

Since then, oil prices have moved up considerably and appear likely to sustain their upward momentum in the short run, given the overall supply situation. Even though supply of petroleum is expected to increase, it may not be sufficient to keep up with demand and keep the rising oil prices at bay.

Since the summer of 2021, we have also witnessed mounting pressure on the price of natural gas, particularly in Europe. The continent relies heavily on natural gas not merely for heating, but also for its electricity generation. Coal power plants are being scrapped and replaced with alternative renewable sources. However, this would be impossible without using natural gas to supplement renewables when necessary. The predicament comes from the fact that Europe has very little natural gas deposits of its own and relies heavily on imports.

To make matters worse, within the context of the global gas supply chain, most competitive gas exports are first routed to other regions of the world, such as China, leaving Europe to buy whatever is left. Also, a large part of the natural gas supplies for the continent come from Russia, which has brought about geopolitical tensions in the past.

Surging bills

Soaring natural gas prices, coupled with a rise in oil prices have already been reflected in higher electricity bills for households across Europe and record high annual inflation figures across much of the western world. This puts pressure on political decision makers, as rising electricity and oil prices are likely to translate into sustained high inflation rates. Some commentators have sardonically borrowed the term “greenflation” to describe this. Coined by billionaire and philanthropist Bill Gates in his book How to avoid a climate disaster, the term describes a premium that is to be paid on environmentally friendly goods and services.

In this context, it is not surprising that the European Commission – alongside its enthusiasm for renewable energy sources such as solar, wind and most recently hydrogen – has also recognised natural gas and nuclear energy as ‘green’ or, at least, as having a crucial role to play in the ongoing process of energy transition.

Shifting focus

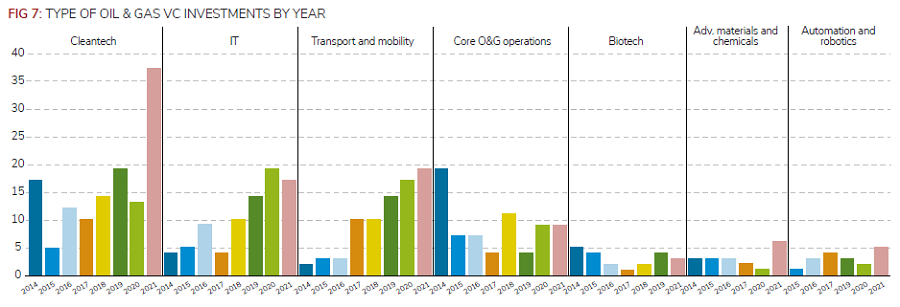

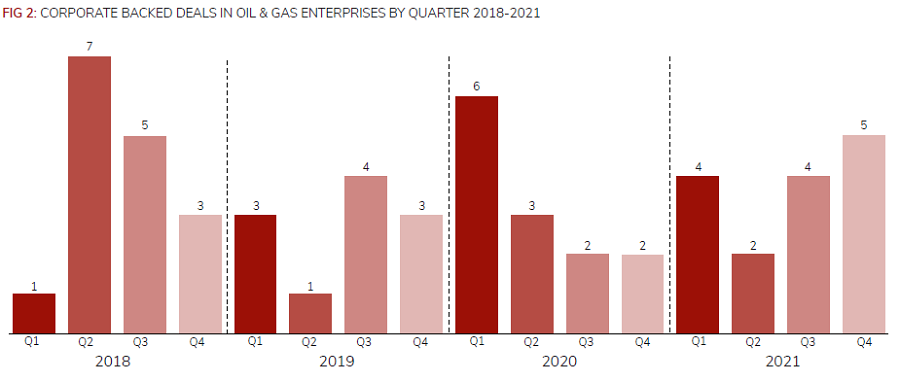

With this as a backdrop, oil and gas majors and their peers have not remained idle in corporate venturing, irrespective of headwinds and tailwinds alike. During the latter half of the past decade, we have seen a shift of focus among oil and gas corporates, still very much evident today and likely to continue to hold in the post-pandemic world. Many of the disclosed deals by such corporate venturers tend to go into emerging businesses from non-core areas, primarily in IT and cleantech, as well as transport and mobility.

Non-core areas in the energy space are considered to be the ones with most disruptive potential to the core business of oil and gas, as low-carbon energy technologies may replace or considerably reduce the reliance on fossil fuels in the future. The increasing adoption of electric vehicles (EV) may also affect a considerable part of the customer base of oil and gas companies. At the time of writing, all major car makers had already started manufacturing EVs. There is an almost unanimous vision that EVs will be the only vehicles at some point in the future. There has also been an increasing digitisation of industrial activities, which exerts a tangible impact on production and efficiency.

However, we expect to see more investments in core oil and gas technologies, particularly in companies whose solutions provide significant cost-savings or make operations somewhat less environmentally damaging. Such investments will continue to form part of the portfolios of corporate venturers from the sector due to its capital-intensive nature, contingent on the up and down swings of commodity prices. Therefore, any innovation enhancing processes and reducing fixed costs are likely to be embraced.

Strategy over finance

In the long run, corporate venturing arms of oil and gas incumbents will most likely continue to be more strategic rather than purely financial in terms of their priorities. In addition to investing in technologies that may profoundly disrupt the sector, strategic benefits may materialise in the form of building an ecosystem, finding suppliers, or helping business units to tackle specific technical challenges.

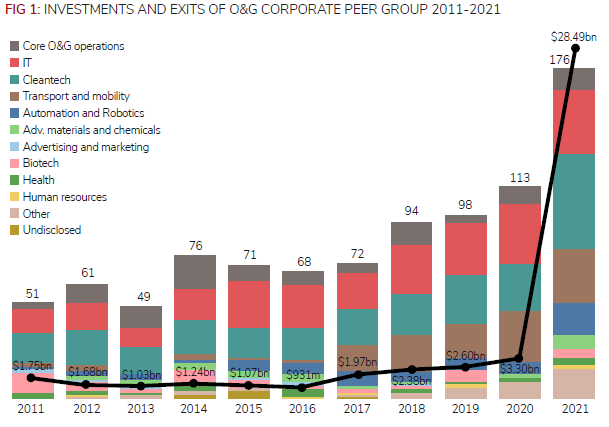

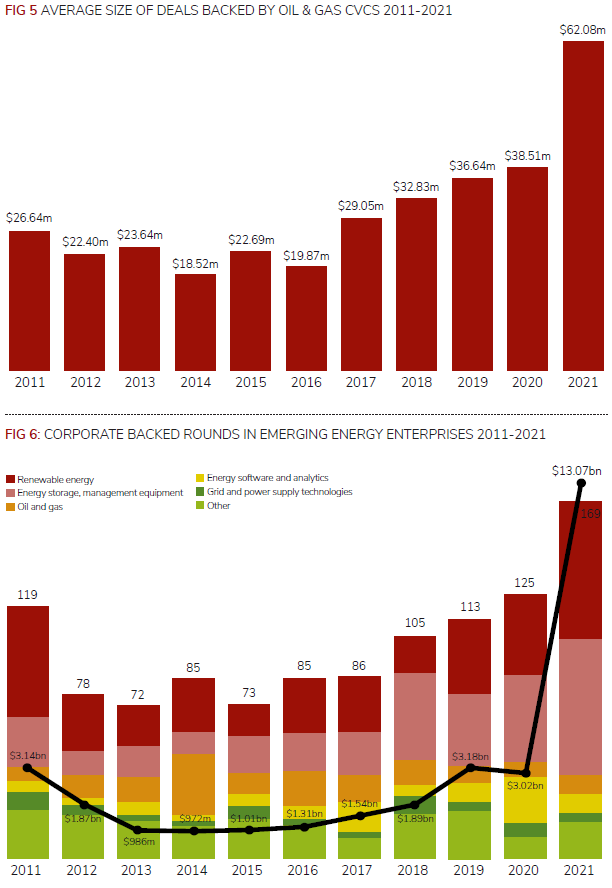

Throughout 2021, we tracked a total of 176 deals, both investments and exits, by the broader peer group of oil and gas corporates and industrials that were worth an estimated $28.49bn. Much like in the overall VC and CVC space, 2021 was a year of hasty and abundant dealmaking and exit activity, which have made figures spike considerably versus previous years. This is also evidenced in the rise of the size of average rounds backed by the industrial and energy peer group of oil and gas majors, which also spiked.

This exuberance can be attributed, in part at least, to the generous monetary policy of near-zero interest rates that has affected all asset classes and was meant to face economic challenges caused by the pandemic. Given current inflationary pressures, this policy is likely to change soon, as the Federal Reserve Bank in the US and other central banks around the globe have already stated their intention to start tapering and increasing interest rates.

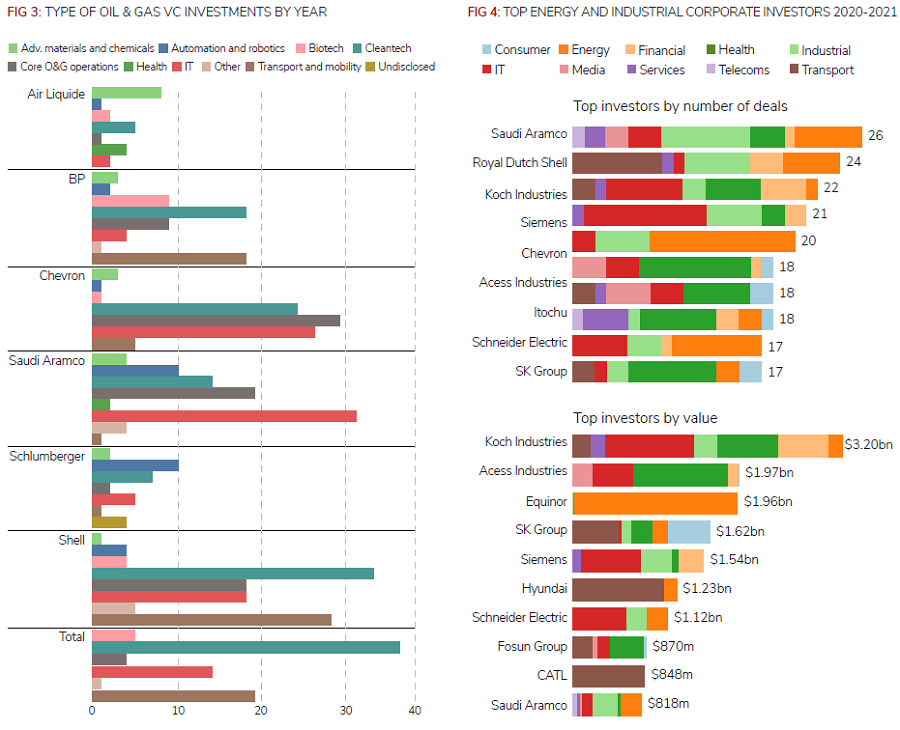

UK-based BP has historically invested in a significant number of rounds in cleantech and transport companies since 2014, along with investments in core operation technologies. France-based Total has bet heavily on cleantech, transport and IT. Anglo-Dutch company Shell has similarly been focused mostly on cleantech and mobility-related technologies, along with IT and core oil and gas applications. US-based Chevron has publicly disclosed commitments revolving around core energy operations, the digital dimension of its operation and, more recently, cleantech. Saudi Arabia-based Saudi Aramco has historically focused its minority stake investments on IT and core technologies and, increasingly, cleantech and automation.

Historical investments

Nearly all oil and gas majors are now somehow involved in the low-carbon and the advanced-mobility opportunities on the venturing scene. Norway-based Equinor (formerly Statoil) boasts two active venturing units – one for low carbon and cleantech investments, dubbed Equinor Energy Ventures (previously known as Statoil Ventures) and another in oil and gas venturing, Equinor Technology Ventures (formerly Statoil Technology Invest). Saudi Aramco has followed in its footsteps with the launch of Prosperity 7 Ventures. Total’s venturing unit had rebranded to Total Carbon Neutrality Ventures and subsequently to TotalEnergies Ventures.