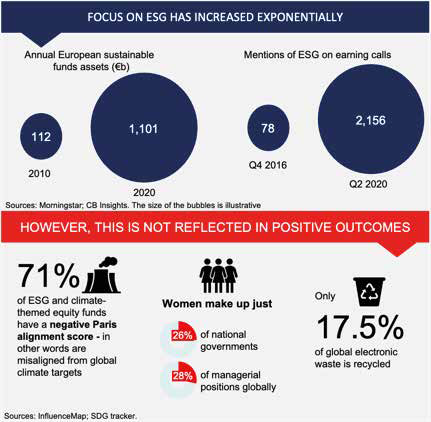

In recent years, executives’ mentions of environmental, social and governance (ESG) on earnings calls has skyrocketed, as has the flow of capital into ESG funds. Bloomberg projects that ESG compliant investments will reach $53 trillion in assets under management globally by 2025 – roughly one in every three dollars of managed assets.

These are large numbers, yes, but they should not come as a surprise – ESG has permeated the conversation across capital markets, private equity, and the rest of the financial services industry. Thanks to new regulations and increased consumer and media interest in sustainable business practices, fuelled by a sense of urgency regarding the climate crisis and the social divides that deepened because of covid-19, ESG reporting has entered the limelight

The demand for a more proactive corporate approach to ESG has transcended informal shareholders’ demands and regulatory guidance to infiltrate every corner of global markets. Now, asset managers, risk assessment teams, and credit agencies have the huge task of navigating evolving regulatory requirements for their portfolios, despite a lack of defined taxonomy and data often being self-reported.

Unfortunately, though, the rise in ESG investments and media mentions have not translated into measurable positive outcomes. Quite the opposite, in fact. After decreasing in 2020 due to dramatically reduced industrial activity and commuting during the pandemic, carbon emissions are expected to rise again in 2021. As the global population has grown over the last decade, so too has both natural resource consumption and the amount of e-waste generated and not recycled.

Furthermore, socially, gender and ethnic parity remains far off, with women and minority groups still having low representation globally in local and national governments, as well as leadership positions in the private sector.

Whether this results from a lag between the adoption of ESG practices and their impact in real economies, ESG practices not having the desired effect, or even having the opposite effect to what was intended, the gap between where things are and where they need to be is clear. Wider industry must reflect on how to accelerate the ESG agenda and, most importantly, focus on impact rather than just discourse.

How can the venture capital community address these challenges?

There are two obvious ways that venture capital can enhance the impact of ESG practices: first, by developing and maintaining a laser-focus on measurable ESG outcomes and directing capital towards those initiatives most likely to deliver (capital allocation), and second, strongly encouraging existing portfolio management teams to think about and, crucially, measure, how their decisions impact a broader base of stakeholders than traditionally considered.

While money is increasingly flowing towards green-finance initiatives, we are still in the early days. A combination of stakeholder pressure, technological advancements, and regulations such as the EU’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), will catalyse rapid innovation in the sector – but much still needs to be done to agree common standards and ways of measuring and reporting on not only financial impact, but a business’ double and triple bottom line.

There are three key areas in this space where there are already investment opportunities: analytics and investing tools; platforms for reporting and compliance; and new ESG assets.

Analytics and investment tools define ESG and sustainability metrics, and screen ESG investments for institutional investors, helping them to cut through potential greenwashing and dig deeper into the impact of their portfolio.

Platforms for reporting and compliance enable companies to better understand and improve their own ESG scores, by tracking the sustainability of their value chains and enabling corporate sustainability reporting. This is particularly useful for large corporates needing to demonstrate compliance with domestic legislation, international regulation, or even investor demands.

Finally, new ESG assets are investment vehicles, such as marketplaces or platforms, that enable retail and institutional investors to allocate funds towards companies having a measurable positive social and environmental impact. This includes green bonds and reforestation and initiatives as well as carbon monitoring and offsetting (a subcategory in its own right).

Beyond capital allocation

VCs also have a role beyond just allocating capital: to support and encourage their portfolio management teams to consider their business’s wider environmental and social impact.

There is a tendency to focus on the environmental and social impact of large corporates, over that of startups and scale-ups. Of course, a company’s ESG strategy will evolve as it matures, and likely become more important as the business grows, but that does not mean that ESG is more relevant to later-stage companies. In reality, it is both easier and more effective to integrate ESG standards and policies from day one, to facilitate the right processes and enable a culture supportive of sustainability to develop. This conflicts with start-ups’ lack of resources and need for focus, especially in the early days of their existence. To some extent, it comes down to venture capital investors’ guidance on how to strike the right balance and incorporate reasonable ESG policies early on.

While we still live in a shareholder-capitalism era, where profit and growth are prioritised over sustainability metrics and wider social good, a shift is clearly underway as shareholder themselves start valuing ESG more and more. A prominent example of this includes Blackrock’s public commitment to monitoring specific ESG key performance indicators for its portfolio companies when considering supporting the re-election of board members. Many other large asset managers are moving in the same direction, although progress is slow. This is because there is increased recognition that while individual asset allocators’ attitudes may change, we must redefine how the market measures success to include non-profit-driven metrics to be consistent with such a change of attitude. Regardless, as investors start focusing on sustainability, business management teams must ascertain how ESG decision-making ties into shareholder value, and how to evaluate and prioritise stakeholder demands.

Sustaining momentum

The factors impairing the impact of ESG – particularly the complexities around data collection and the lack of measurement and reporting standards – will not come as a surprise to those familiar with sustainability initiatives. Many of the tools and technologies we need to achieve positive ESG outcomes already exist or are being developed by entrepreneurs and funded by venture capitalists as we speak.

It all starts with standards and having a generally agreed North Star to aim towards, but the globality required for those standards is hard to achieve and could take a generation or two to materialise if we had the time – which we do not. To reach that point before it is too late, isolated and self-initiated practices must be gradually integrated into a single framework (or a reasonably small amount of non-contradictory frameworks) that will stand both the passage of time and the practical needs of international industry. This will be the only way to secure global buy-in.

Hopefully, regulators will develop standards while individual businesses take increasing action of their own volition. In particular, the “experimentalist governance” model advocates for smaller institutions and governments to set binding standards that catalyse change, such as California’s vehicle pollution state laws that pushed manufacturers to increase their focus on electric vehicles. Only then, when top-down and bottom-up solutions converge, will the global ESG agenda be able to effectively solve the different problems our environment and societies are facing.