A month ago, cryptocurrency exchange FTX was a $32bn company and CEO Sam Bankman-Fried was one of the most respected names in the industry. It filed for bankruptcy today alongside quantitative crypto trading firm Alameda Research and 130 other affiliates, its assets frozen by regulators.

Investors including corporates SoftBank, Circle and Coinbase have been burned along with its customers, and Bankman-Fried has resigned. So, what went wrong, and what does it mean?

Founded in 2019 and registered in the Bahamas, FTX was the third largest digital currency exchange in the market by volume. In 2021, at the height of cryptocurrency trading, it recorded $388m in net income from over $1bn in revenue.

The company’s growth was fuelled by some $2bn in venture funding, $900m of which came from backers including SoftBank, Coinbase and Circle at an $18bn valuation in July 2021. All three joined Binance in a $421m round just three months later, valuing it at $25bn. It added another $400m in January.

FTX even acted as a white knight in July this year when it offered a $400m credit line to crypto management tool producer BlockFi to prevent it going bankrupt. It was viewed as a leading candidate to clean up in any consolidation period.

But like many businesses in the crypto sector, FTX also operated its own tradeable crypto token, FTT, which was where this saga began.

What the hell happened?

FTX was incubated in Alameda Research, which was founded by Bankman-Fried. But CoinDesk obtained documents last week indicating that $5.8bn of the quant firm’s $14.6bn assets consisted of unlocked FTT and FTT collateral. A firm being so heavily leveraged is one thing, for it to be through a currency created and controlled by its sister company is another.

Changpeng Zhao, CEO of rival Binance – itself an early FTX investor – tweeted on Sunday that his company was divesting all its FTT, panicking investors and driving the price of the coin from about $25 last week to under $5 by Tuesday. It stands at $2.62 at time of writing.

Binance signed a letter of intent to acquire FTX on Tuesday but withdrew as soon as it saw the company’s financials. FTX backers Sequoia Capital and Paradigm Capital then marked down the value of their shares, worth a combined $491m, to zero, while Bankman-Fried sought $8bn in financing to cover withdrawal requests.

But why would a cryptocurrency exchange need cash to allow users to withdraw their money?

The reason became clear yesterday when a source told the Wall Street Journal that FTX had lent $10bn of its customers’ money to sister company Alameda – a business, remember, which held a big part of its assets in FTT, now virtually worthless. Bankman-Fried announced yesterday Alameda Research would wind down.

Although Bankman-Fried also claimed sister company FTX US, backed by SoftBank’s Vision Fund 2 at an $8bn valuation, is a separate entity with completely liquid assets and therefore unaffected by the turmoil, the offshoot announced yesterday it could halt trading next week.

“I’m sorry,” he said in a Twitter thread. “That’s the biggest thing. I fucked up, and should have done better.”

What does it mean?

FTX’s investors

The collapse of FTX will almost certainly hit its customers hardest, but the failure of a company – now publicly labelled worthless by multiple backers – is also a blow to its shareholders.

SoftBank’s Vision Fund 2 invested in its last three rounds, including a January round giving it the $32bn valuation, but its exposure is nothing like it was to Uber or WeWork. A source told Bloomberg today it expects to lose less than $100m, though the situation represents a further setback on a day when the fund posted a $7.2bn quarterly loss.

Circle, the operator of both a peer-to-peer payment platform and a stablecoin linked to the US dollar, has FTX as both a portfolio company and an investor, but CEO Jeremy Allaire said on Wednesday those stakes were “tiny” and assured users it had never taken FTT as collateral.

Binance, already the world’s largest exchange, may have lost some equity cash but the bigger concern would have been how much of the the $529m in FTT it held could be offloaded. It arguably comes out better having removed a key competitor from the table but, as with Coinbase (the second largest exchange), the issues go deeper because of how the affair will impact public perception of digital currencies and their viability.

Portfolio companies

FTX wasn’t just a startup, it was also an active corporate VC. Bankman-Fried launched FTX Ventures in January this year with $2bn in capital and it has accrued a portfolio of more than 40 companies, with yet more backed by its parent.

The unit invested a total of about $350m this year, in deals including a $350m round for Near Protocol and Mysten Labs’ series B round, which increased to $300m this week. But its portfolio won’t be left high and dry.

A person familiar with the matter told The Information it has already wired that cash to the startups, though the CEO of portfolio company LayerZero Labs said it bought back its stake this week.

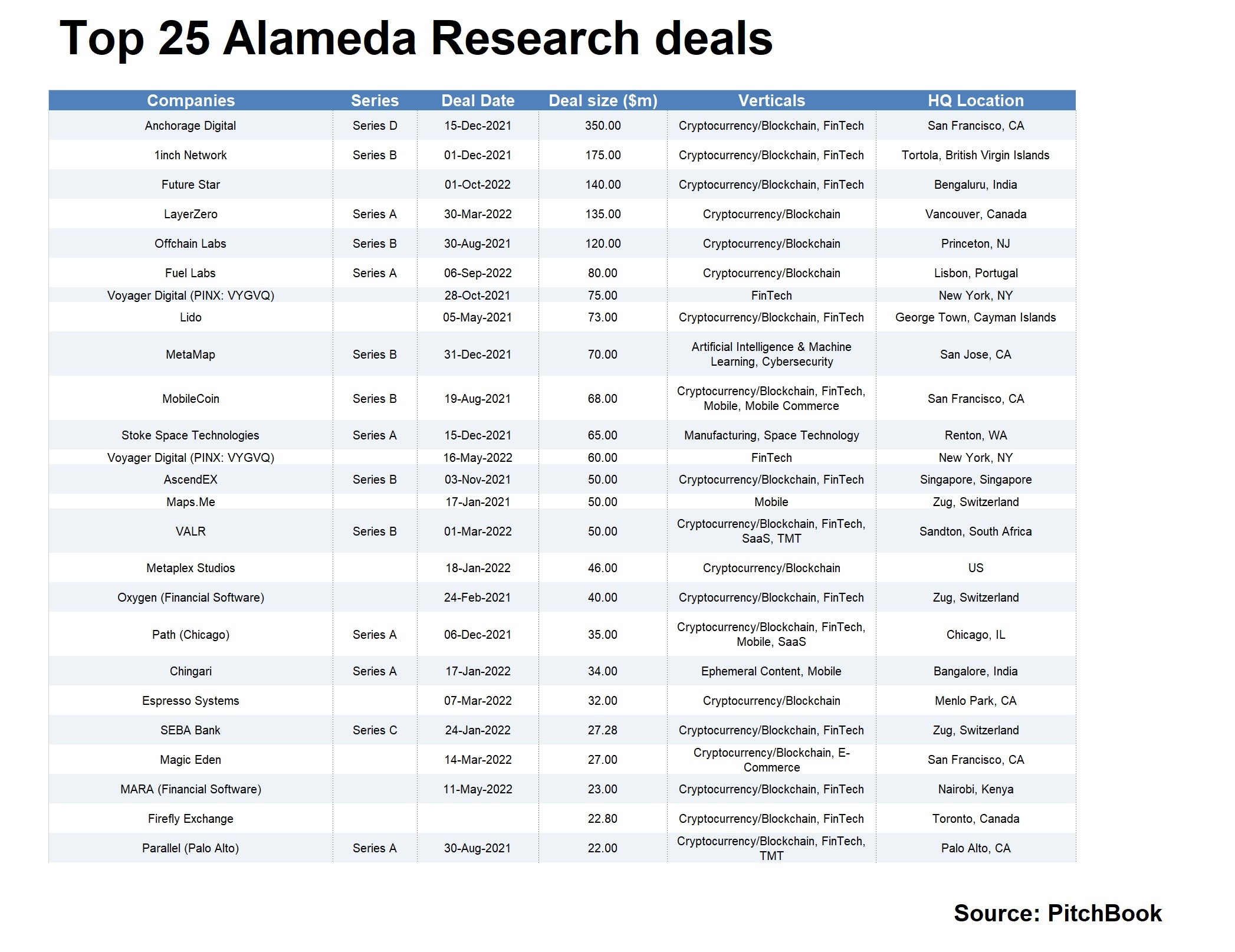

The status of Alameda’s VC holdings is less clear, but it has been one of the most active investors in the sector, building a portfolio topping 160, the largest deals listed below.

With both firms urgently now needing to pay back customers, its equity stakes in these companies may represent the most viable asset they have. Will more businesses seek to buy back their shares, perhaps at a discount, or will other firms seek to pick up some bargains?

In any case, the exit of two such active investors marks a blow to the crypto VC scene, which is already dealing with a substantial fall in deal flow this year, heightened by an earlier string of crashes in May that took in crypto hedge fund Three Arrows Capital and stablecoin issuer Luna.

The wider cryptocurrency sector

Bankman-Fried’s companies were regarded as among the most stable in the crypto sector and potentially capable of building an empire as rivals fell away.

The rapid rate at which they have unravelled impacts the very idea of investing in digital tokens, which spells trouble if, like Binance or Coinbase, your revenue relies on commission from those trades.

In a wider sense, many investors fear contagion. The fact the third largest crypto exchange had the two above it as investors indicates just how interconnected the industry is, with many of its companies providing debt financing, investing or buying tokens in each other.

When Three Arrows defaulted on a $650m loan to digital currency exchange Voyager Digital in June before going bankrupt, it pushed Voyager into insolvency. Crypto app developer Solana is one of several owners of tokens propped up by Bankman-Fried in recent years, and the price of its SOL coin has halved this week. How many investors have holdings in SOL as well as FTT?

The main crypto tokens, including Bitcoin, Ethereum and Binance’s BNB coin, have all fallen around 20% in price this week. With each of these setbacks a warning sign to outsiders, questions have to be raised about the long-term viability of the sector. What happens if another big operator goes down and it spooks token holders into a market-wide rush?

As far as the wider Web3 ecosystem goes, some investors have been suggesting for a while that the flashier elements such as cryptocurrency and NFTs may have to be separated from the more usable technologies such as blockchain and decentralised finance. This collapse may have hastened this process.

PayPal Ventures, GV, American Express Ventures and SCB10X are among the corporate units that have gone biggest on the sector, though their deals largely remain in the single figures. We may now see them moving more definitively into the technology side of Web3, but one thing’s for sure: no one’s going to be skipping time on due diligence.