“The eyes, it has been said, are windows to the soul. I would argue that the real portals are the ears,” said Poppy Crum, chief scientist at Dolby Laboratories and an adjunct professor at Stanford University, in her seminal 2019 article for IEEE Spectrum.

Indeed, the ear has been described as the USB port to the body, emotions and external world in ways that are even more effective than through the eyes, as they can touch and stimulate the vagus nerve that helps your speed of learning, or plasticity.

How we develop our senses will arguably shape how we succeed as people, both individually and as nations. Augmenting ourselves through artificial intelligence will come with extending our sense of smell, touch, taste, hearing and sight to improve the inputs the brain receives, alongside new forms of data through human-brain interfaces.

Such technology-target neuroplasticity will enable us to think more effectively, make faster and better decisions, and train and recover more optimally. The outcome will be greater speed and connectivity in our brains and the world.

It will also effectively enable the creation of ‘digital twins’. Just as they are used in architecture and engineering to model scenarios and run training against live action scenarios, the same will increasingly be true to help, say, air traffic controllers train their neural pathways and improve interpretation of data.

Improved human insight and action will come with increased frequency and resolution of data from sensors in a feedback loop between the human and technology.

Better understanding

As historian Yuval Harari said in an interview on ethics with Tristan Harris for Wired: “The real key is whether somebody can understand you better than you understand yourself.

“It is extremely irresponsible that… you can have a degree in computer science and coding and you can design algorithms that now shape people’s lives, without having any background in thinking ethically and philosophically about what you are doing” (see Ethical artificial intelligence ecosystem, page 8).

Through this understanding from technology comes the ability to apply neuro-marketing, to make advertising more effective by eliciting a greater emotional response.

The consumer ecosystem, with its abundant sensors on and in our bodies through phones, wearables and implants have become windows to the subconscious and evolutionary pressures mean companies can race to use this personal data unless privacy regulations intervene.

As VC firm Lux Capital said when selling CTRL-labs to Facebook (now called Meta) in 2019: “[It] has created a transformative brain-machine interface that picks up the neural signals within the body to control devices outside of it, with little more than natural gestures. The next step is non-invasively reading the intention from the brain – no gestures required.”

Healthy market

Wearables, such as smartwatches and fitness trackers can record more than 7,500 physiological and behavioural variables, according to a survey by the Economist.

In 2015, when Apple launched its first watch (which within four years was selling more than the entire Swiss analogue watch industry), was the year corporate venturing activity in the health wearables and monitoring device market also took off.

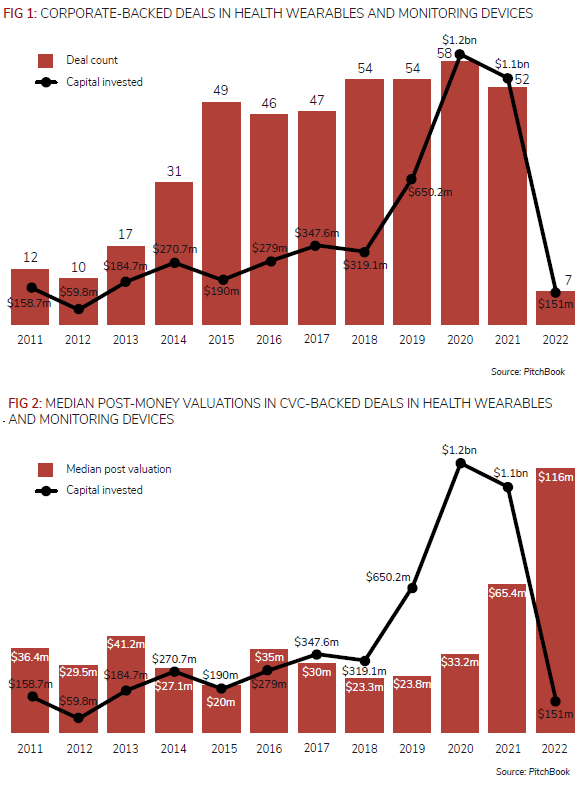

There was a more than 50% jump in deal volume that year compared with 2014, according to PitchBook data. Investment by value has climbed since then to more than $1bn in each of the past two years, while sales of smartwatches and fitness trackers more than tripled in this period to $29bn from $8bn, according to market-research firm ccs Insight.

In 2021, it was estimated that about a quarter of US and British citizens owned a smartwatch or fitness tracker and 400 million devices a year are expected to be sold globally by 2026, up from 200 million in 2020, according to the Economist.

There are now more than 400,000 health and wellness apps on the Apple and Google app stores, with 250 added daily. The problem is that people do not just need a product that is well designed, they need a product that is well designed for them, says Liz Ashall-Payne from Orcha, a British organisation that evaluates the quality of health apps for clients, including the National Health Service in the UK. As she pointed out to the Economist, buying a pair of trousers online is made easy by filters for size, colour and style, but no such system exists on the app stores. A teenager seeking help for anxiety will need a different type of app to his grandparent wanting the same thing.

Wearables, apps and artificial intelligence in combination look set to reshape healthcare through more personalised medicine, as well as earlier diagnoses and treatment.

The US spends $10,000 to $20,000 per year per patient with diabetes and about $280bn a year nationally, half the entire public-school budget, according to the Economist. A diabetes-control app monitoring blood-sugar levels and personal behaviours has been shown to reduce the cost per patient by $1,400 to $5,000.

The covid-19 pandemic meant many people had to be monitored at home for health reasons, closing the gap between how people are viewed when trying to stay healthy or when they are sick.

The Economist said: “On the one hand, they are making life more medicalised, with people, for the first time, keeping an eye on things such as their nocturnal heart rate. On the other hand, they are ushering in a shift in the balance of responsibility between medical treatment provided by clinicians and what patients do to improve their own health.

“About 80% of the burden of disease in America is caused by lifestyle factors and many poorer countries are not far behind. Drugs work as intended in only 30-50% of people. For many diseases there are no therapies at all.”

Across the generations

Doctors in the US and Europe are seeing more elderly patients with smartwatches that relatives have bought for them in order to track their health and send alerts of any problems, the Economist reported.

Smart devices, therefore, serve as a platform for innovators. “Within a year or two, the device on your wrist may be measuring non-invasively your blood sugar, alcohol and hydration, as well as various markers of inflammation, kidney and liver function – all of which currently require blood to be drawn,” the Economist said.

Market analysts told the Economist that, in the next five years, the wearables market would split into two categories: medical-grade devices approved by regulators for people with chronic conditions who need tracking with greater care and accuracy, and devices with less sophisticated features for healthy people who want to keep an eye on their metrics and be able to spot problems early.

Combining wearables with apps, such as Blue Star for diabetes or Perfood for migraines, means people are more aware what a particular meal, bedtime schedule or exercise does to their blood sugar, with advice on what they should change. This makes them more effective than the most widely used drugs alone.

Sensors and algorithms are becoming more sophisticated, turning wearables into diagnostic devices able to indicate if a person’s walk or voice is an indication of early-stage Parkinson’s disease or depression, or whether temperature sentiment changes can indicate pregnancy.

Since 2017 the US Federal Drug Administration has approved more than 40 health apps for problems as varied as diabetes, back pain, opioid addiction, anxiety, ADHD and asthma. They are reviewed under the rules for medical devices, usually in the moderate-risk category (which covers things such as pregnancy tests and electric wheelchairs), the Economist said.

It concluded: “Wearables… make it possible, for the first time, to take the temperature or measure the pulse of a population rather than an individual.”