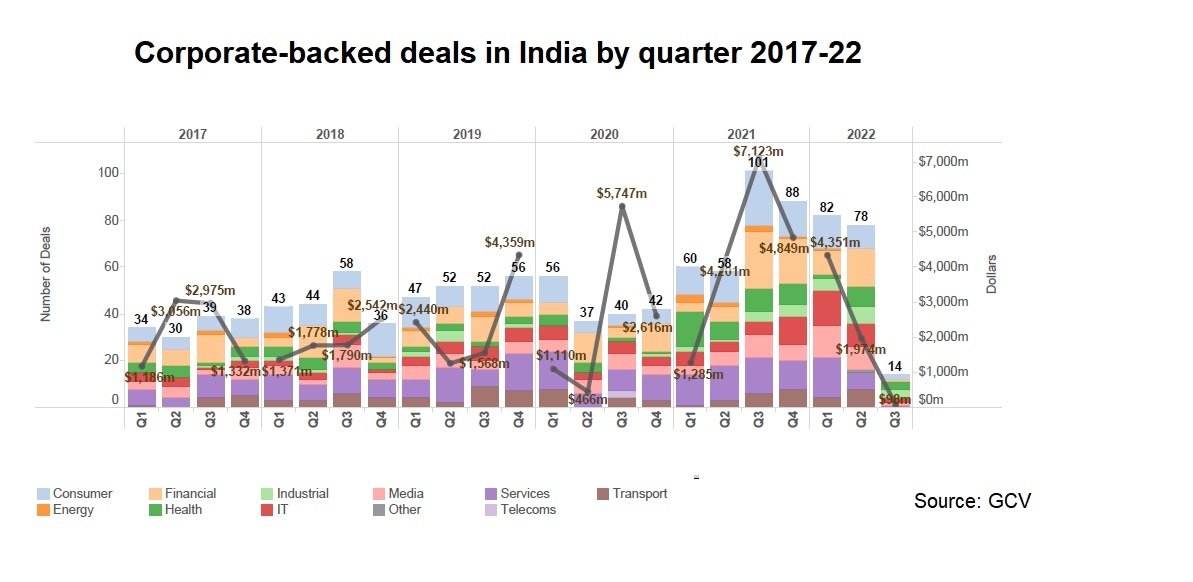

The amount of capital raised by India-based companies in corporate-backed rounds fell by more than half in the second quarter of this year despite deal volume staying resolute, GCV data indicates.

Companies secured a total of approximately $1.97bn for the quarter, down from $4.35bn in Q1 2022 and representing only 28% of the cash raised in Q3 2021. However, the deal count numbered 78, down only slightly from 82 and comfortably higher than in any quarter ever before the second half of last year.

Preliminary figures from Q3 show the figure for both columns is set to drop further, evidence of a slowdown in funding from many domestic corporates, as the country becomes more reliant on foreign corporates, in turn leaning away from hard tech to consumer-facing businesses.

Foreign investors are still making their presence felt

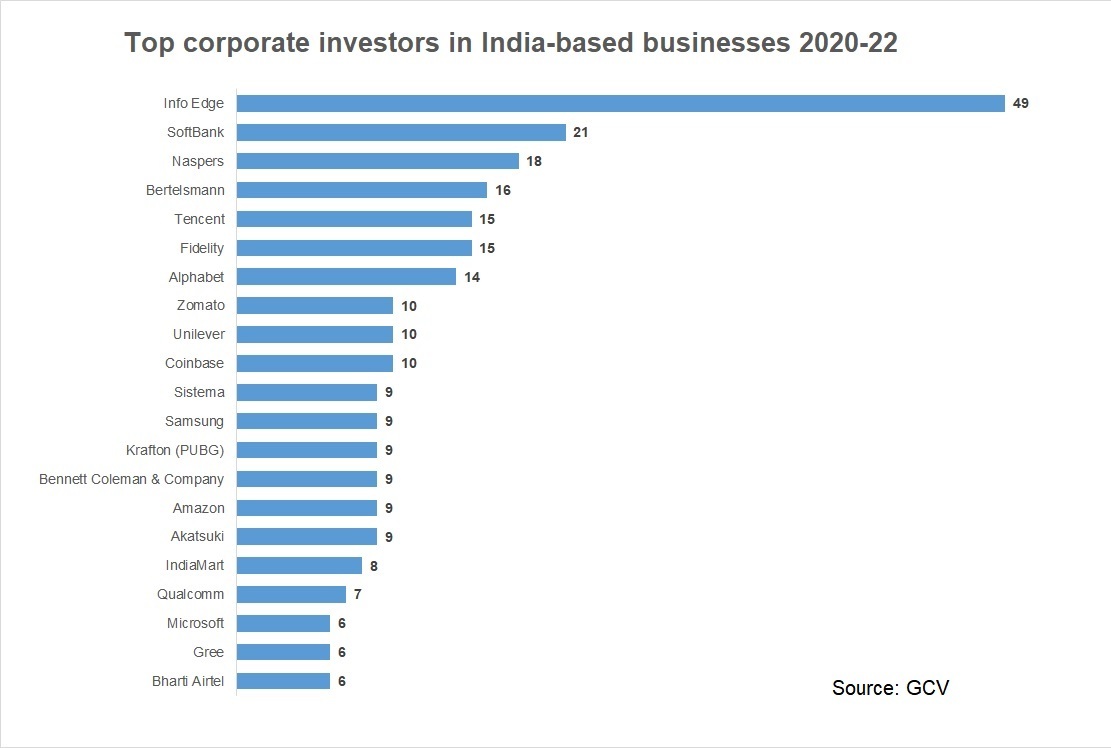

Much of the corporate funding for Indian startups continues to come from foreign sources, with eight of the 10 biggest corporate investors since the start of 2020 located outside the country. This interest was recently exemplified by Germany-based media group Bertelsmann pledging $500m in capital for its Bertelsmann India Investments (BII) unit.

Bertelsmann is one of the four highest corporate investors in India-based companies during that period according to GCV data, trailing only Info Edge, SoftBank and Naspers/Prosus in a top 10 that also includes fellow internet groups Tencent and Alphabet and consumer goods producer Unilever. It’s worth noting SoftBank, Tencent and Naspers were prominent in most of the Indian startup space’s biggest successes in the last wave of online companies, heavily backing the likes of Flipkart, Oyo, Byju’s and Ola pre-IPO.

Only five of the top 21 CVC investors are actually based in India, and the country’s corporate venturers can essentially be split into two main groups: domestic-focused investors who are predominantly focused on consumer-facing businesses, and international investors such as Infosys and Wipro which tend to target enterprise and edge technologies.

A startup scene still leaning towards consumer offerings

The divide is down to the structure of India’s economy. The country recently overtook China to become the world’s most populous country and will likely overtake the UK to become its fifth largest economy by the end of this year.

That’s a huge customer base, and it’s reflected by its biggest corporate investor, classified listings operator Info Edge, which oversees a portfolio led by food delivery service Zomato and insurance comparison platform Policybazaar, both of which went public in 2021.

Info Edge formed its own venture capital vehicle, InfoEdge Ventures, in mid-2020, and the unit has invested in more than 20 companies since then, but all are consumer-focused and only two are located outside India. Info Edge’s direct investments have also largely been consumer-focused, though it has backed AI-focused startups LegitQuest and CynLr in the past 18 months.

Perhaps the best traditional synthesis of the two models is that of Times Internet, formed over two decades ago as Indian media group Bennett Coleman & Co (BCC)’s online business.

The unit has backed the likes of online automotive marketplace CarDekho, social media platform ShareChat and online education provider Byju’s at home while using BCC’s market presence to strike deals with large international companies looking to enter India, such as Uber, Airbnb and Coursera, acquiring equity stakes through strategic or commercial partnerships.

Newer consumer tech companies are also getting in on the act. Food delivery services Swiggy and Zomato have each made a string of investments in areas like e-commerce offerings, restaurant management software and urban logistics providers.

These companies also have the means to link portfolio companies to a vast network of restaurants that could become their customers. However, Zomato announced in May this year it was pausing direct investments. Times Internet meanwhile has visibly cut its investment activity in the past year.

Indian corporates divided between inward and outward views

Although corporate venture as a whole has never quite made the breakthrough in India it has elsewhere in Asia, some of the country’s largest multinationals still maintain dedicated investment subsidiaries. The problem is they’re often situated overseas and concentrate more on ‘hard tech’, and they barely look at India.

The contrast can be seen in the below table, with several key investors not even on the India investors chart above:

To give an example of how this works, IT services firm Wipro and steel producer Arcelor Mittal have VC units, but they’re situated in Silicon Valley and London respectively. Wipro peer Infosys’ Innovation Fund is located domestically but its portfolio is still predominantly based overseas.

The impression is that there is a firm divide between the two models, but it wasn’t always the case. Conglomerates Reliance Industries and Tata were frequent early-stage investors in India’s nascent tech sector in the last decade, but both have subsequently slowed their pace.

Reliance ended up acquiring four of its domestic portfolio companies, spanning areas like enterprise resource planning, drones and conceptual learning technology. Tata on the other hand shuttered its Tata Capital Innovations Fund and has only made two early-stage investments in the past two years.

And it can be hard to be a strategic fund for a multinational if you’re based in India. Biplab Adhya of Wipro Ventures recently told Global Venturing that 75% of Wipro’s customers are in the US or Europe, so when you’re offering to hook portfolio customers up with big corporate clients, proximity counts.

“We need to be close to where our customers are so we can help them with the solutions we invest in, and where the startup ecosystem is more prominent, where enterprise innovation is happening,” he said.

“Silicon Valley is the most logical choice for that. The other thing is that we have a very small team and we cannot spread ourselves across the globe.”

University spinout gap emblematic of a larger issue

The gravitation of India’s startup sector as a whole away from pure technology and towards consumer-facing startups can be reflected in the relatively low number of businesses spun out of university research, according to Global University Venturing editor Thierry Heles, who points to an early 2021 study indicating the lack of experience in that space.

“A majority of universities in the country had only two to five years of experience in commercialising intellectual property, and only 17% of the respondents had a track record of more than a decade,” the report states. “India’s government only proposed a bill to commercialise university research in 2008. A third of universities saw fewer than 10 academic invention disclosures, the foundation for spinouts and licences, in five years.”

Heles adds: “While there is potential, and funds like the $100m robotics-focused vehicle launched by Indian Institute of Science and AI Foundry-founded Artpark mean capital would be available, the relative lack of experience in tech transfer means the country remains behind its international peers in terms of spinouts.”

The university issue is important because it points to a gap at very early stage, one that could be helped by corporate incubator or accelerator schemes. However, the only prominent scheme by a domestic corporate was BCC’s now closed TLabs accelerator, with the rest helmed by foreign companies like Microsoft and Target.

The fact deal numbers are holding steady while round totals drop does point to early-stage activity, but it generally tends to be led by dedicated early-stage firms like Better Capital and Titan Capital or US venture firms like Sequoia Capital and Accel, with corporates tending to tag along.

The retreat of domestic giants like Reliance, Tata and automotive manufacturer Mahindra from early-stage investing is largely feeding the divide. If an Indian company like Wipro bases its corporate VC arm in Silicon Valley, what incentive is there for a large corporate group in Europe or the US to hunt out Indian technology?

Most of the big foreign corporates also rarely invest at seed stage in India because they don’t have the local infrastructure to find those small deals. The consumer focus of domestic businesses meanwhile means they are more susceptible to market downturns like the current one.

For the Indian VC space to remain strong long term, it needs the country’s largest companies to look internally for strategic technology bets.