We focus on hazards attributed to intellectual property (IP) regimes in particular and, even more specifically, forced” technology transfer (FTT) policies.

Among the risks that IP regimes pose to foreign MNCs, those related to appropriability appear to be most directly relevant to FTT policies.

“Appropriability” is the ability to protect knowledge from imitation via some form of monopoly, which allows economic returns from such knowledge to be captured. Or, somewhat more broadly, the term refers to the ability of a firm to capture, as it chooses, the profits generated by its knowledge.

IP regimes are an important tool to ensure appropriability. So-called “appropriability hazards” are often present in a host market when inadequate protection of IP rights – usually because of “voids” in IP institutions – enables leakage of technological knowledge.

Meanwhile, on the other end of the spectrum, excessive or otherwise suboptimal institutional structures in IP regimes can also create appropriability risks. For example, excessive legal appropriability afforded by the IP regime to some firms can sub-optimally limit the appropriability of other firms.

Further, the state’s aggressive/excessive use of institutions, such as anti-trust regulation over IP monopolies, can also create appropriability hazards.

FTT policies appear to be an example of the excessive use of institutions rather than the previously mentioned forms of appropriability hazards often attributed to “weak” IP regimes.

We choose to focus on China in this paper because it is a hotspot for FTT policies that appear to be of growing concern to MNCs whose value chains are increasingly dependent on China. For example, the US Trade Representative [in 2018] found that “while these [FTT] policies and practices [in China] are not necessarily new, their actual and potential effects on foreign companies and their technologies have become much more serious”.

FTT policies in China can take various forms, including: (1) “Lose the market” policies (including market access preconditioned on meeting technology transfer requirements); (2) “No choice” policies (including unfair IP civil litigation rulings, and de facto requirements to excessively divulge trade secrets to receive regulatory approvals and then sharing that information with competitors); and (3) “Violate the law” policies (for example, appropriability-weakening legal provisions governing the interface between anti-trust and IP, IP and technical standards, and the import and export of technology).

Foreign MNCs who have committed to and invested in China during a time when FTT policies were less damaging, or who have increasingly dispersed upstream and downstream value chain activities in China, are acutely affected by the shift in bargaining power facilitated by China’s FTT policies at present.

For example, in 2017, some US technology companies derived over 80% of their global revenues from China (Goldman Sachs, 2018). Foreign MNCs appear heavily exposed to China’s FTT policies: for example, in 2017, at least one fifth of firms answering the European Union Chamber of Commerce’s Business Confidence Survey reported they had to transfer technology in China as a precondition to gain market access

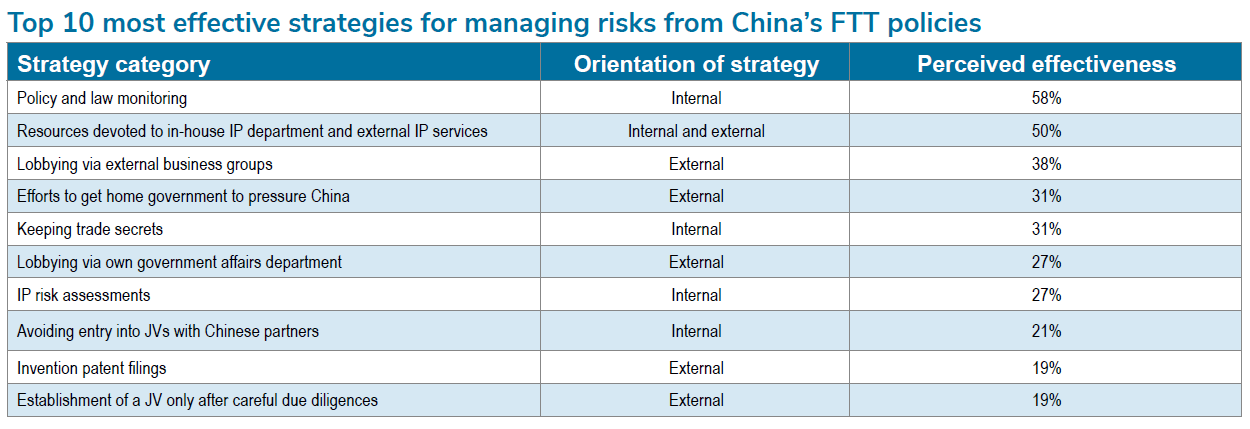

Between 2013 and 2017, we collected empirical data via a survey of 106 of which top five strategies (34 total listed) “worked best for mitigating the detrimental effects” posed by Chinese FTT policies in the last five years. Interviews with 42 Western MNCs followed the survey about the design of Chinese FTT policies and how foreign MNCs respond to them. Then, to update our research, in 2019 we reviewed laws, government reports, and other sources to provide a discussion of events that have transpired since the start of the recent US-China trade war, which is substantially fuelled by foreign MNCs’