Burning fossil fuels, whether coal, oil or gas, releases its carbon content and the energy transferred can be used for electricity or heat. And while such sources of high power have long been in demand, many people are becoming increasingly concerned about the carbon emitted and its effects on climate change and so are turning to startups through corporate venturing to fund renewables – such as hydro, nuclear, microbes, solar and wind – and to find efficiency measures, as well as ways to capture or limit carbon emissions.

But with the sheer abundance of potential solutions being tried and supported, whether microbes for biofuel, nuclear fusion, geothermal and wind, solar and hydrogen power, comes two vectors for allocating resources by investors.

First, potential to move the needle to reach zero emissions. Second, the time needed to get to positive unit economics.

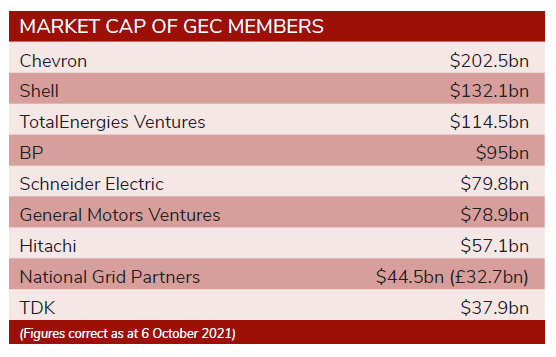

The Global Energy Council (GEC), representing 10 corporate venture capital (CVC) units on behalf of parent companies with aggregate market capitalisation of almost $850bn as at 6 October, has taken these two vectors. During the past year, under the stewardship of Lisa Lambert at National Grid Ventures, the council has applied them to 20 areas of innovation to develop working groups and identify the technologies that could deliver the greatest opportunities to reach zero emissions in the earliest time for a positive financial return. The message ahead of the COP26 meeting next month, framed by the GCV Symposium in the UK, is that corporate venturing often works best when it allies strategic and financial goals to the benefit of society and its providers of capital.

Strategic aims

CVCs invest in areas that are most strategic to their corporate parent. The word “strategic” has different meaning to each CVC, but all corporates in the GEC do align on one metric, their inclination to reach zero emission goals as soon as possible. Different innovations catalyse zero emission goals to varied extents and hence this is one of the critical parameters that we used to obtain a more normalised outcome.

CVCs also invest in areas that generate solid financial returns, referred to many as ‘venture-style’ returns. The CVC working group thought the factor that drove this venture-style financial return was the unit economics of the product or service, as it measures profitability. Areas that are profitable faster are more likely to see such venture-style growth.

Route map to sustainability

When thinking about next-generation mobility – one of the core users of energy and one of the four targeted areas of innovation – the council came up with a targeted approach for governments and other investors to consider when planning a technological route map out of unsustainable climate change.

Council members in a group organised by Anil Achyuta at TDK Ventures and Galina Rachenkova at Hitachi Ventures selected logistics and electric vehicles – also covering financing, infrastructure and recycling – as the likely highest-performing investments to deliver net zero emissions within five years.

The areas of highest-potential impact that could take more than a decade to deliver positive net unit economics included hydrogen-powered vehicles (despite potential niche uses in heavy industry, such as steel-making and trains), mining, air travel and ‘smart’ cities.

Innovation requires time and resources and energy groups and societies often plan their capital expenditure over years and decades. Knowing where the most impactful levers to get to net zero are in segments promising the best financial returns is an important component for envisioning the future.

The next series of GEC quarterly reports will cover the implications from production (this issue) through storage, distribution and demand, and track how the billions of dollars being invested in helping match intention to limit climate change, with the realities of what innovators can achieve and for what society is willing and able to pay.